Primer: U.S. Deportations—Executive Power

The executive branch has been given broad authority to enforce immigration law and conduct mass deportations. These authorities come from historical precedent, the U.S. Constitution, and statutes passed by Congress. The president of the United States can use every mechanism of power available to facilitate the removal of those who are present in the United States illegally.

Background

While Congress has plenary power over immigration law, the Immigration and Nationality Act, Homeland Security Act (HSA), and other immigration statutes grant the executive branch substantial discretion when carrying out immigration policy, including deportations.1 When the executive branch performs these functions, in most cases it does so via the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).2 Several other agencies, however, share in the responsibility for carrying out immigration law and policy, including components of the Departments of Justice, State, Health and Human Services, Labor, Interior, and Treasury, along with the Federal Land Management Agencies.3

Under the first Trump administration, the United States enjoyed robust executive policy actions regarding illegal aliens. Over the course of his first four years in the White House, President Donald Trump and his administration issued 472 executive actions on immigration.4 Almost immediately upon assuming office in January 2021, however, President Joe Biden reversed nearly all of those successful policies and replaced them with a de facto open border policy that allowed millions of illegal aliens to enter into the United States.5

Now that Trump has emerged victorious in the 2024 presidential election and has been sworn in as president of the United States, he has an opportunity to fully restore and expand the process of deporting illegal aliens and secure our border through the use of executive power. The executive branch of the United States government has broad powers and authorities that it could invoke under President Trump’s leadership.

Executive Immigration Authority

Prior to the ratification of our Constitution, the English common law recognized the sovereign of state (in this usage defined as “the civil government of a country”) as having the inherent prerogative to deport aliens.6 Drawing from the law of nations, Sir William Blackstone summarized the inherent deportation powers of a state’s chief executive as follows:

[I]t is left in the power of all states, to take such measures about the admission of strangers, as they think convenient; those being ever excepted who are driven on the coasts by necessity, or by any cause that deserves pity or compassion. . . . [S]o long as their nation continues at peace with ours, and they themselves behave peaceably, [foreigners] are under the king’s protection; though liable to be sent home whenever the king sees occasion.7

Blackstone’s Commentaries, particularly the seminal volume concerning public law referenced herein, were treated as authoritative by the Framers of the Constitution.8 His endorsement of the universally applicable legal principle that each sovereign possesses the inherent power to deport aliens from that sovereign’s territories was widely shared by scholars of the law of nations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.9 This principle still applies today, and, as described above, Congress has plenary power over immigration,10 with executive immigration authority mainly derived from congressional delegations of that authority. Congress has provided substantial discretion to the executive branch regarding the administration of immigration law, including that of the deportation of illegal aliens.11

Agency Breakdown

Federal agencies have overlapping responsibilities over immigration enforcement and deportations. The following departments and their components fulfill these responsibilities.

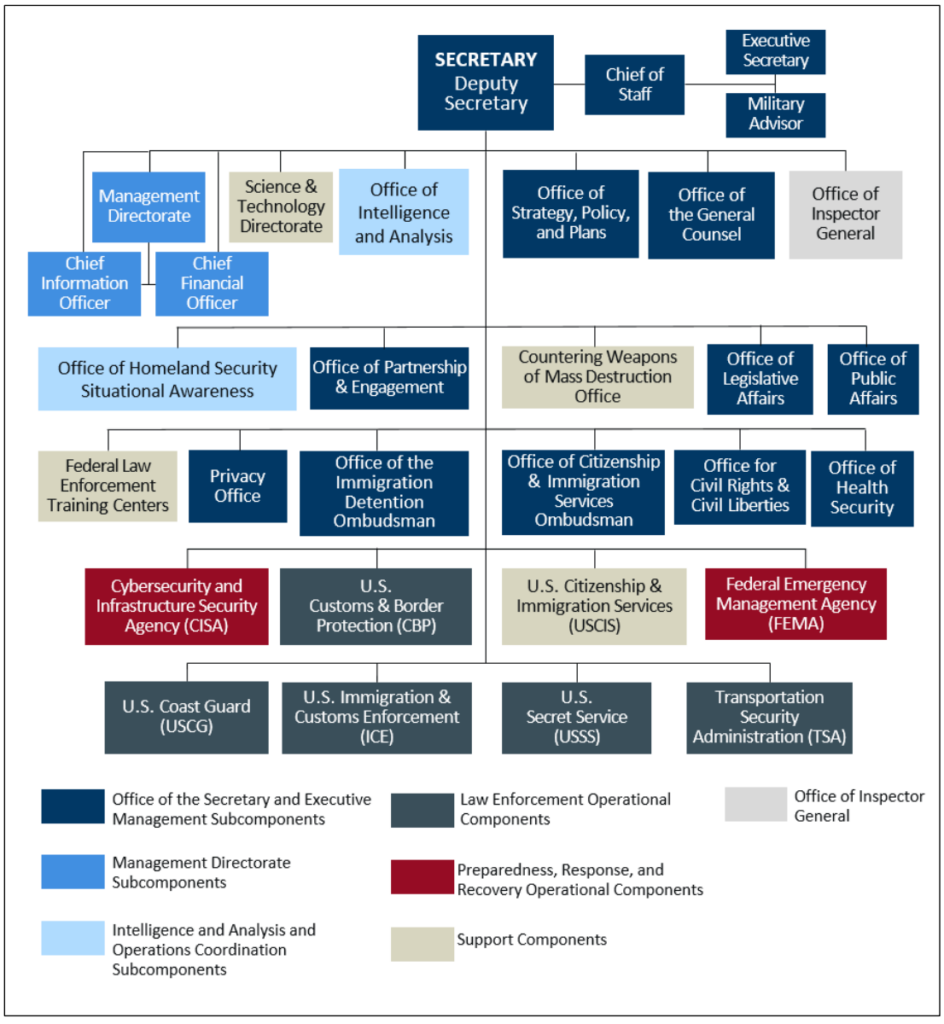

Department of Homeland Security

DHS was established under the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (HSA).12 The HSA abolished the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which was a part of the Department of Justice (DOJ).13 It transferred many of the INS’s functions to the new DHS, a cabinet-level department incorporating twenty-two federal agencies and components.14 Three DHS agencies are responsible for immigration and enforcement functions: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).15

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

USCIS oversees lawful immigration to the United States, including adjudicating applications for naturalization, visas, and work permits.17 USCIS asylum officers also conduct credible fear screenings for certain aliens who intend to apply for asylum.18

Immigration and Customs Enforcement

ICE is a law enforcement agency within DHS that is primarily responsible for immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior.19 Within ICE, Enforcement and Removal Operations identifies, arrests, detains, and removes foreign nationals who are unlawfully present or removable.20 According to the Congressional Research Service, ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) also conducts federal criminal investigations of people, goods, money, technology, and contraband, both in the interior and along the border.21 In recent years, HSI has attempted to distance itself from ICE by focusing on transnational crime rather than immigration enforcement.22 The Trump administration could consider directing the agency to refocus on cracking down on illegal immigration and drug cartels.

Customs and Border Protection

CBP enforces immigration laws at U.S. land, air, and sea borders by processing arriving aliens.23 Within CBP, the Office of Field Operations (OFO) operates at U.S. ports of entry, and OFO officers inspect travel documents and determine whether arriving aliens are admissible.24 The U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) secures the border between ports of entry and has responsibility for the detection, prevention, and apprehension of individuals who have entered or are attempting to enter the United States without authorization.25 USBP operates within geographic-based sectors at the northern, southern, and coastal borders.26

Processing Deportations in DHS

USCIS, ICE, and CBP can charge foreign nationals in the interior or at the border with grounds of deportability and inadmissibility and process them for removal from the United States.27 DHS commences formal removal proceedings when it issues a Notice to Appear (NTA) charging document and files it in an immigration court.28 ICE’s Office of the Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) represents DHS during removal proceedings.29 It is important to note that the Biden administration significantly slowed the issuance of NTAs, and as more deportations are conducted more OPLA attorneys will be needed.30 Consideration could be given to developing a corps of advocates as accredited representatives who have not necessarily gone to law school but who can prosecute ordinary and less complicated cases. There is no statutory requirement that ICE’s prosecutors must be full-fledged attorneys. But 8 C.F.R. 1292 would need to be amended to allow non-attorneys to represent the government in immigration proceedings.31 This would speed recruiting, introduce cost savings, and add substantial flexibility to the agency, allowing it to handle higher caseloads.

Department of Justice Executive Office for Immigration Review

Within the Department of Justice, the Executive Office for Immigration Review’s Office of the Chief Immigration Judge operates the nation’s immigration court system.32 Immigration Judges adjudicate immigration court proceedings, which are civil administrative proceedings and include removal proceedings that DHS commences as described above.33

Additional Departments

- Department of State: The Department of State (DOS) is responsible for issuing immigrant and nonimmigrant visas at U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide to foreign nationals outside the United States.34 DOS also plays a significant role in obtaining permission for the United States to return removable aliens to their home countries and determining the punishments for countries that allow illegal immigration to the United States.35 In the past, DOS has been unwilling to impose meaningful punishments on recalcitrant countries, and the Trump administration could change that practice. The example of President Trump’s threat of tariffs to Columbia for not taking back its citizens36 was effective and would lead one to expect the DOS under President Trump to—for the first time—adopt a similarly aggressive stance.

- Department of Health and Human Services: The Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) provides additional resettlement assistance to newly arrived refugees, asylees, and certain other eligible groups. This includes the care and custody of unaccompanied children apprehended by DHS while they await removal proceedings.37 At an April 2023 House Oversight and Accountability Committee hearing, the Biden administration’s ORR director could not answer questions about reports that show HHS has lost contact with more than eighty-five thousand migrant children.38 President Trump has also claimed that the Biden administration has lost track of nearly three hundred thousand unaccompanied children, a statement that is based on numbers cited in an August 19, 2024, report prepared by the Office of Inspector General for DHS.39 The Trump administration could consider investigating this failure and dismiss the officials responsible for it.

- Department of Labor: Employers seeking to hire foreign nationals through permanent immigration categories or temporary nonimmigrant programs must first obtain labor certification from the Department of Labor’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification.40

- Department of the Treasury: Remittances, the transfers of money sent by noncitizens to their home countries, may be subject to sanctions under various federal statutes administered by the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. The U.S. government restricts remittances to countries, individuals, or companies that are subject to U.S. sanctions and embargoes.41 The possibility of taxing remittances also has frequently been raised at both the state and federal levels. If this tax is implemented at the federal level, it would be implemented by the Department of the Treasury.42

- Federal Land Management Agencies: Most of the relevant agencies in this group (the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Reclamation) reside under the Department of the Interior, which owns large portions of land near both the northern and southern borders and manages various territories.43 The U.S. Forest Service falls under the Department of Agriculture.

Selected Executive Actions

President Trump began his second term on January 20, 2025, by imposing sweeping executive actions that overturned the Biden administration’s de facto open border policy, reimposed successful policies from his first administration, and helped begin the process of mass deportations. Here are some of the actions the Trump administration has taken:

- President Trump has declared a national emergency and is deploying military personnel to the border.44 The president has powers that may be exercised if the nation is threatened by crisis or emergency circumstances, such as an invasion at the southern border.45

- President Trump has also directed the Secretaries of Defense and Homeland Security to finish the wall along the southern border.46

- President Trump has ended the so-called practice of “catch and release,” which allows illegal aliens waiting for immigration cases to be adjudicated to be released in the interior of the United States.47

- The Migrant Protection Protocols (also known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy), which require illegal aliens to be returned to Mexico and wait outside of the United States for the duration of their immigration proceedings, has been restored.48

- The Biden administration’s mass parole process for Cubans, Nicaraguans, Haitians, and Venezuelans has been halted.49

- President Trump has issued an executive order to end birthright citizenship of noncitizens unlawfully present in the United States.50

- President Trump has directed the hiring of more ICE and CBP officers and required the establishment of DHS task forces that include federal, state, and local law enforcement.51

- President Trump has created a process to designate transnational cartels, including Tren de Aragua and MS-13, as foreign terrorist organizations, subjecting their members to deportation under the Alien Enemies Act (AEA).52

Alien Enemies Act

President Trump has also suggested invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, which authorizes the president to arrest, imprison, and deport all “natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects” of hostile foreign nations as “alien enemies” during times of war, invasion, incursion, or threats thereof.53 According to the Center for Immigration Studies, the AEA was enacted in reaction to a feared invasion by France, then in the middle of the chaos of the French Revolution.54 The federal government used the act during the War of 1812 and during the first and second world wars, when the U.S. detained thousands of alien enemies.55 Federal courts, including the Supreme Court, have upheld the AEA’s constitutionality.56 President Trump could use this vital tool to remove illegal alien criminals and gang networks that are poisoning children with fentanyl and terrorizing the streets of American cities.

The Threat of Cartels

It is important to note that the president possesses all necessary powers under the Constitution, the Insurrection Act, the Military Cooperation with Civilian Law Enforcement Officials Act, and other federal statutes to secure the U.S. southern border and to prevent the continued invasion of the United States by deploying the military. The cartels may attempt to impede these efforts, and the Center for Renewing America has made thorough legal arguments57 regarding the ability of the Trump administration to put the military to work on the border (as the Trump administration has already done) and laid out phased plans for how the military might engage to counter and eradicate the cartels if needed.58

Conclusion

The executive branch has been given broad authority to enforce immigration law and conduct mass deportations. These authorities come from historical precedent, the U.S. Constitution, and statutes passed by Congress. The president of the United States can use every mechanism of power available to facilitate the removal of those who are present in the United States illegally. President Trump has indicated that he will do so, and every federal employee and appointee must support him in this noble effort.

Endnotes

1. Straut-Eppsteiner (June 7, 2023). “Immigration 101: Executive Branch Agencies Involved with Immigration,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12424

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Press Release (February 1, 2022). “Trump Completed 472 Executive Actions on Immigration During His Presidency, Many That Could Have Lasting Effects on the U.S. Immigration System,” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/trump-472-executive-actions-immigration-during-presidency

5. Camarota, Zeigler (May 13, 2024). “Foreign-Born Population Grew by 5.1 Million in the Last Two Years,” Center for Immigration Studies. https://cis.org/Report/ForeignBorn-Population-Grew-51-Million-Last-Two-Years

6. Peter L. Markowitz, Deportation Is Different, 13 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 1299, 1309 (2011) (“Legal historians agree that the . . . power[ ] to exclude or prevent entry[ ] could be exercised by the king alone without any criminal process. In regard to the power to expel noncitizens from within England, there is some disagreement, as a theoretical matter, as to whether the power could be exercised through civil administrative fiat or solely through the criminal process. As a practical matter, however, the historical record demonstrates that expulsion was exercised exclusively as a common form of criminal punishment in England (imposed on both citizens and noncitizens) as early as the thirteenth century.”)

7. 1 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England *259–60 (1765).

8. See M.J.C. Vile, Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers 112 (1998).

9. See, e.g., Emer de Vattel, The Law of Nations: Or, Principles of the Law of Nature, Applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns, bk. I, ch. XIII, § 162 (1758) (“The sovereign may forbid the entrance of his territory either to foreigners in general, or in particular cases, or to certain persons, or for certain particular purposes, according as he may think it advantageous to the state. There is nothing in all this, that does not flow from the rights of domain and sovereignty: every one is obliged to pay respect to the prohibition; and whoever dares to violate it, incurs the penalty decreed to render it effectual.”)

10. See Kleindienst v. Mandel, 408 U.S. 753, 766 (1972) (“The Court without exception has sustained Congress’ ‘plenary power to make rules for the admission of aliens and to exclude those who possess those characteristics which Congress has forbidden.’” (quoting Boutilier v. INS, 387 U.S. 118, 123 (1967))); Oceanic Steam Navigation Co. v. Stranahan, 214 U.S. 320, 343 (1909) (discussing “the complete and absolute power of Congress over the subject [of immigration]”); Galvan v. Press, 347 U.S. 522, 531 (1954) (holding that “policies pertaining to the entry of aliens and their right to remain here are peculiarly concerned with the political conduct of government” and “the formulation of these policies is entrusted exclusively to Congress”).

11. Straut-Eppsteiner (June 7, 2023). “Immigration 101: Executive Branch Agencies Involved with Immigration,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12424

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Painter (March 21, 2023). “The Department of Homeland Security: A Primer,” The Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47446

17. Straut-Eppsteiner (June 7, 2023). “Immigration 101: Executive Branch Agencies Involved with Immigration,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12424

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Miroff (April 15, 2024). “Homeland Security Investigative Agency Seeks Rebrand, Without ICE,” Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/2024/04/15/homeland-security-immigration-customs-enforcement/

23. Straut-Eppsteiner (June 7, 2023). “Immigration 101: Executive Branch Agencies Involved with Immigration,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12424

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. Staff Report (October 24, 2024). “Quiet Amnesty: How the Biden-Harris Administration Uses the Nation’s Immigration Court’s to Advance an Open Borders Agenda,” House Committee on the Judiciary. https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/judiciary.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/2024-10-24%20Quiet%20Amnesty%20-%20How%20the%20Biden-Harris%20Administration%20Uses%20the%20Nation%27s%20Immigration%20Courts%20to%20Advance%20an%20Open-Borders%20Agenda.pdf

31. It should be noted that nongovernmental organizations are already allowed to advance individuals as accredited representatives to appear and practice before the courts and in the immigration proceedings of DOJ and DHS. (See 8 C.F.R. § 1292.12.)

32. Straut-Eppsteiner (June 7, 2023). “Immigration 101: Executive Branch Agencies Involved with Immigration,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12424

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. Wilson (July 10, 2020). “Immigration: ‘Recalcitrant’ Countries and the Use of Visa Sanctions to Encourage Cooperation with Alien Removals,” Congressional Research Service.

36. Garcia Cano, Suárez, Miller (January 26, 2025). “White House Says Colombia Agrees to Take Deported Migrants After Trump tariff Showdown,” Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/colombia-immigration-deportation-flights-petro-trump-us-67870e41556c5d8791d22ec6767049fd

37. Straut-Eppsteiner (June 7, 2023). “Immigration 101: Executive Branch Agencies Involved with Immigration,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12424

38. Hearing Wrap Up (April 18, 2024). “Hearing Wrap Up: ORR Director Fails to Answer Questions About 85,000 Lost Unaccompanied Alien Children, Flawed Vetting of Sponsors, and More,” House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. https://oversight.house.gov/release/hearing-wrap-up-orr-director-fails-to-answer-questions-about-85000-lost-unaccompanied-alien-children-flawed-vetting-of-sponsors-and-more%EF%BF%BC/

39. Farnsworth (September 16, 2024). “HHS Stonewalls FOIA Request on ‘Lost’ Migrant Children,” Center for Immigration Studies. https://cis.org/Farnsworth/HHS-Stonewalls-FOIA-Request-Lost-Migrant-Children

40. Straut-Eppsteiner (June 7, 2023). “Immigration 101: Executive Branch Agencies Involved with Immigration,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12424

41. Weiss (May 10, 2024). “Remittances: Background and Issues for the 118th Congress,” The Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R43217/16

42. Cadman (January 23, 2017). “Remittance Tax to Fund the Wall?,” Center for Immigration Studies. https://cis.org/Cadman/Remittance-Tax-Fund-Wall

43. Vincent, Comay, DeSantis, Nardi, Riddle (October 7, 2024). “The Federal Land Management Agencies,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10585

44. Proclamation (January 20, 2025). “Declaring a National Emergency at the Southern Border of the United States,” The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-a

45. Webster (November 19, 2021). “National Emergency Powers,” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/98-505

46. Proclamation (January 20, 2025). “Declaring a National Emergency at the Southern Border of the United States,” The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-a

47. Executive Order (January 20, 2025). “Securing Our Borders,” The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/securing-our-borders/

48. Ibid.

49. Ibid.

50. Executive Order (January 20, 2025). “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship,” The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/protecting-the-meaning-and-value-of-american-citizenship/

51. Executive Order (January 20, 2025). “Protecting the American People Against Invasion,” The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/protecting-the-american-people-against-invasion/

52. Executive Order (January 20, 2025). “Designating Cartels and Other Organizations as Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Specially Designated Global Terrorists,” The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/designating-cartels-and-other-organizations-as-foreign-terrorist-organizations-and-specially-designated-global-terrorists/

53. An Act Respecting Alien Enemies, ch. 66, 1 Stat. 577 (1798).

54. Fishman (October 10, 2023). “The 225-Year-Old ‘Alien Enemies Act’ Needs to Come Out of Retirement,” Center for Immigration Studies. https://cis.org/Report/225yearold-Alien-Enemies-Act-Needs-Come-Out-Retirement

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. Policy Brief (March 25, 2024). “The U.S. Military May Be Used to Secure the Border,” Center for Renewing America. https://americarenewing.com/issues/policy-brief-the-u-s-military-may-be-used-to-secure-the-border/

58. Primer (October 11, 2022). “It’s Time to Wage War on Transnational Drug Cartels,” Center for Renewing America. https://americarenewing.com/issues/its-time-to-wage-war-on-transnational-drug-cartels/