A New Force Posture for the Middle East

Executive Summary

- The Greater Middle East is a region beset with ancient rivalries and societal challenges that the U.S. cannot fix in a top-down manner either through force of arms or other nation-building efforts. It is of declining strategic importance for the U.S., with no immediate or long-term hegemonic threats or near-peer rivals.

- Current American force posture in the region is increasingly difficult to sustain in an era of multipolarity.

- The U.S. has lost thousands of lives and spent trillions of dollars on fruitless nation-building wars in the Middle East that ultimately empowered our adversaries in the region – mainly Iran.

- Local threats such as terrorism and hostile small states are not existential threats to the U.S. and can be properly managed with a more focused strategy. Nothing in the region warrants a large-scale, permanent forward presence.

- The U.S. should narrow its priorities in the region to maintaining a regional balance of power, keeping sea lanes open, and preserving a limited counter-terrorism mission focused on groups that have the intent and capability to harm American interests. This will enable the United States to free up resources for more critical priorities.

The 2017 National Security Strategy stated that the U.S. “seeks a Middle East that is not a safe haven or breeding ground for jihadist terrorists, not dominated by any power hostile to the United States, and that contributes to a stable global energy market.”1 This has been the bipartisan Middle Eastern strategy since the Carter administration. The logic is simple. A hostile power dominating the entire region would result in it having enormous leverage over both critical sea lanes as well as precious commodities such as oil. The strategic interest of the United States in regard to the Middle East is therefore limited to preventing a local hegemon, keeping the sea lanes open, and eliminating local terrorism threats with the intent and capability to harm American interests.

This policy brief charts the threat profile of the region from terrorism and potential peer rivals. It demonstrates that the U.S. faces no hegemonic challenge from any potential peer or near-peer rival in the region and is of declining strategic importance to the U.S., especially when compared to other parts of the world. The brief then highlights the overextension in the region by post-Cold War American administrations, including the invasion of Iraq, a proxy war in Syria, and carrying the main financial burden of the war against ISIS. The brief then outlines the cost to the U.S. to maintain the current force posture and strategy. It identifies the potential threats of distinct local hostile powers as well as terror organizations. Finally, it argues for an alternative strategy. The threats in the Middle East can be minimized by a combination of balancing strategies, a limited naval presence, and long-range strike capabilities.

In many ways, this is a return to the Middle East approach of the Nixon Administration. President Richard Nixon argued for local actors to take the “primary responsibility of providing the manpower for [their] defense” and that the United States would “furnish military and economic assistance when requested in accordance with our treaty commitments.” 2 A new force posture and strategy for the Middle East in an era of emerging multipolarity should not be rooted in ideological impulses; rather it would mirror Richard Nixon’s idea, allowing for local foot soldiers to take the lead in maintaining the regional balance of power, deterring threats to sea routes, and absolute non-interference in the social and national development in the region.

Threat Scenario and Interests in the Middle East

The region’s social problems are myriad. Its ancient tribal, ethnic, and religious divisions are well documented. It is also of declining strategic importance to the U.S.3

The GDP of the region is roughly one-third of the total GDP of the European continent and around one-eighth of Asia.4 The region is sparsely populated by comparison, which has historically made it difficult for one regional state to have the capacity to dominate the entire theatre.5 The prime commodity of the region – oil – is fungible. There is ample evidence to support the notion that the region is of declining importance to the U.S. given the ability to achieve American energy independence and shifting strategic priorities.6 To use one particularly pithy summary, it is a “small, poor, weak region beset by an array of problems that mostly do not affect Americans— and that U.S. forces cannot fix.” 7

There are however, three strategic interests – and potential strategic threats – for the U.S. in the region. Primary among them is to ensure freedom of navigation in the high seas and open trade routes, particularly through the Gulf of Aden, Strait of Hormuz, and through the Suez Canal. This is an American hangover from the British imperial strategy of maintaining maritime freedom of navigation, typical of naval great powers dependent on sea trade. There are some arguments that an American retrenchment from the region might propel other great powers to assume an outsized role in the region.8 First, while it is not in America’s interest to have the sea routes that join Europe and Asia to fall under the security umbrella of an adversarial great power (i.e. China or Russia), the chances of that happening are minimal. It is also possible that market shocks would result from the closure of Middle Eastern sea lanes by a peer or near-peer rival would harm American economic interests. Once again, however, there is no realistic possibility of that happening anytime soon. China has recently made forays into Middle Eastern diplomacy, but no realistic military assessment demonstrates that the Chinese can currently muster the needed naval power and the required logistical support to sustain lengthy, large-scale military operations long distances from their core area of operations in East Asia. Russian naval forces are bottled up in the Black Sea, with a rump presence in Syria’s Mediterranean ports. At present, neither China nor Russia is willing, nor truly capable of establishing Middle Eastern hegemony.9

Second, it is in America’s interest to ensure that Islamist terrorist groups that possess both the intent and capability to harm the United States can be targeted effectively. But not every group with localized intent but lacking global reach should be America’s concern.

America’s decade-long investment in Iraq collapsed with the pitiful performance of the American-funded and trained Iraqi army in the face of the ISIS assault, just as the region’s experiment with Madisonian multi-ethnic “democracy” crashed and burned in the fires of historical, ethnic rivalries.10

Nevertheless, the rise and fall of ISIS also demonstrated that expansionist powers almost always invite balancing.11 ISIS was extraordinarily successful in rapid state formation and an initial regional blitzkrieg, but starved of manpower and production capability, it collapsed when faced with a regional balancing coalition of established states. These states were often at odds with each other during peacetime but were all focused on defeating ISIS the moment it became an expansionist threat. During peak ISIS expansionism, the international coalition spearheaded by the United States under the Combined Joint Task Force of Operation Inherent Resolve included the U.S., Canada, Australia, Belgium, France, Denmark, and the UK, alongside Jordan and Saudi Arabia. 12 Other powers at war with ISIS either overtly or covertly outside the U.S.-led umbrella included the rump state of Syria under Bashar Assad, Russia, and Iran.

Currently, the terror threats originating from the region are relatively low and manageable. 13 Additionally, many of these groups – in particular, the scattered remnants of ISIS – pose a greater threat to Iran than to American interests. The U.S. failed in ideologically transforming a hostile region. It cannot, as some scholars argued, “fundamentally alter this permissive environment for terrorism and chaos without investing in state building at a level far beyond what either the American public or broader foreign policy considerations would allow.”14

Terrorism is, therefore, a permanent threat to be mitigated, which can be achieved with a minimal forward presence, local forces, human intelligence, advanced “over the horizon” strike capabilities, and surveillance technology. 15

Finally, America has an interest in preventing a local power from establishing regional hegemony. This has been a vexing issue for American presidents for over fifty years and was what initially drove the United States into the Middle East in a significant way in the 1970s’, along with the spectre of increasing Soviet influence the region.

The Abraham Accords, a series of normalization agreements between Israel and traditionally hostile Arab states, facilitated a regional balancing coalition aimed towards Iran. For many nations in the region, Iran is still considered a major local threat. The Iranian regime (as opposed to the Iranian people) is also quite obviously opposed to American hegemony. However, Iran’s GDP and military capacity is not enough for the country to aspire for a local hegemony.16 In addition, Iran is a Shia Muslim theocracy in a region largely dominated by countries with Sunni Muslim majorities – further constraining its ability to become a regional hegemon.

Threat is intention plus capability. The Iranian state is balanced in the region by both qualitatively and numerically superior Israeli and Arab conventional forces along with nuclear arsenals maintained by Israel and Sunni-majority Pakistan (which has a historically close military relationship with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s primary Arab competitor). In short, the idea of Iranian hegemony, at least in the near future, is improbable.

An Alternative and Prudential Strategy

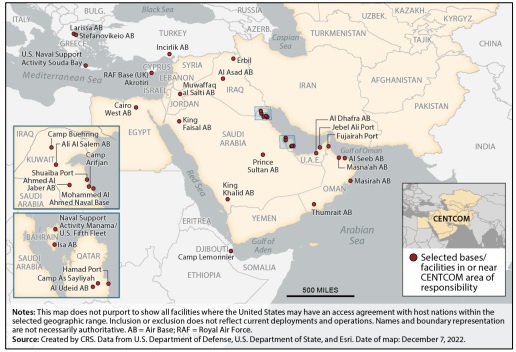

In 1998, the United States had around 27,000 active-duty forces stationed in the Middle East, compared to 1978, when the United States had only around 3,000 troops. 17 There are currently approximately 60,000 troops based in the region (with the number fluctuating somewhat based on troop rotations) spread out across nearly a dozen countries including Iraq, Syria, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Oman.

The current U.S. Middle East force posture costs the American tax payer around $50 to $70 billion annually. The cost of the global war on terror since the United States invasion of Afghanistan currently stands at $8 trillion, with a total cost of military intervention in Iraq and Syria standing at around $2.1 trillion and around $355 billion more for forward presence in other countries.18

The U.S. overstretch in the Middle East that began even prior to 9/11, especially when compared to the relative post-Cold War drawdowns from Europe and Asia, cannot be explained without the ideological dimension of American foreign policy.19 The post-Cold War American presidential administrations (with the exception of President Trump) were all bipartisan followers of some version of “liberal hegemony” that dictates that spreading democracy – either through foreign aid, civil society building efforts, or by military force – is to the long-term benefit of American foreign policy.20 The policy implementation of that theory has proven to be disastrous.

The invasion of Iraq and toppling of Saddam Hussein, support for the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, the Libyan intervention in 2011, and the proxy war in Syria, as well as the constant call for regime change in Iran, all stem from an ideological commitment to liberal interventionism.21

The threats emanating from the Middle East are not existential in any measurable way. There is no global terrorist network that can topple the American government or attempt regional hegemony after forming an expansionist state. The local and potentially belligerent powers of the Middle East are all similarly broken financially. American investment in trying to strengthen Middle Eastern civil society has not produced any measurable benefits but has increased local hostility and resentment.22

Therefore, the primary objectives for an American presence in the region should be limited to maintaining a capacity to deter any regional hegemons, maintain open sea lanes, and to strike terrorist groups with the intent and capability to harm American interests. This can be accomplished with a very limited forward presence, just as it was prior to the first Gulf War.

The American naval presence in Bahrain – which has existed in various forms since the 1970s – should be maintained to provide infrastructure to support naval operations in the region. A regional counter-terrorist force with long-range surveillance and strike capabilities should also remain in the Greater Middle East. As needed, additional deterrence can be provided by long-distance bomber flights (i.e. B-52 and B-2 bombers) in times of heightened tensions.23 Additionally, a U.S. Navy Carrier Strike Group or a U.S. Navy/Marine Corps Amphibious Ready Group can be sent into the region to provide additional capability as needed (although trade-offs against other priorities should be carefully weighed).

Beyond what is required to maintain those capabilities, the American military force posture in the Middle East should be drawn down – including from the ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Syria.

Conclusion

The United States is no longer an unrivaled power living in an age of unipolarity. It now has real competitors—China —along with domestic economic and fiscal challenges that necessitate difficult trade-offs in foreign policy.

Considering the larger failure of American foreign policy in the Middle East over the last 20 years and the declining strategic importance of the region compared to others like East Asia, the United States should significantly de-prioritize the Middle East as a national security focus. This does not mean undertaking a complete retrenchment, but instead recognizing that the United States must better husband its power and no longer squander it in the sands of the Middle East.

ENDNOTES

1. “National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” The White House, December 2017.

2. See, Richard Nixon, “Informal Remarks in Guam With Newsmen,” American Presidency Project, July 25, 1969, available at https://www. presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/informal-remarks-guam-with-newsmen; and Richard Nixon, “Address to the Nation on the War in Vietnam,” UVA Miller Center Presidential Speeches, November 3, 1969, available at https://millercenter.org/ the-presidency/presidential-speeches/november-3-1969-address-nation-warvietnam.

3. For a brief idea of how divided the Middle East is, see the introduction to the Heritage Foundation’s 2022 Index of U.S. Military Strength, Middle East.

4. World Economic Outlook, April 2022. IMF

5. World Population Prospects 2022, United Nations

6. See, David Blagden and Patrick Porter, 2021 “Desert Shield of the Republic? A Realist Case for Abandoning the Middle East”, Security Studies; Martin Indyk, January 17, 2020, “The Middle East Isn’t Worth It Anymore”, Wall Street Journal; Charles L. Glaser and Rosemary A. Kelanic, 2017, “Getting out of the Gulf”, Foreign Affairs; Emma Ashford, 2018, “Unbalanced: Rethinking America’s Commitment to the Middle East,” Strategic Studies Quarterly

7. Justin Logan, 2020, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East”, Defense Priorities

8. Martin Indyk, January 17, 2020, “The Middle East Isn’t Worth It Anymore”, Wall Street Journal

9. David B. Larter, “With Iran Tensions High, a U.S. Military Command Pushes a Dubious Carrier strategy,” Defense News, March 24, 2020, and Jason Sherman, “Senior DOD official: Additional Patriot force structure may be needed to meet demand,” Inside Defense, December 9, 2021.

10. Eric Schmitt and Michael Gordon, “The Iraqi Army Was Crumbling Long Before Its Collapse, U.S. Officials Say,” New York Times, June 12, 2014; Vanessa Williams, “Defense Secretary Carter: Iraq’s Forces Showed ‘no Will to Fight’ Islamic State,” Washington Post, May 24, 2015

11. Stephen M. Walt, 1990, “The Origins of Alliances”, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs

12. See, Operation Inherent Resolve, details available at https://www.inherentresolve.mil/

13. See, “Report: Terrorism on Decline in Middle East and North Africa” available at https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/report-terrorism-decline-middle-east-and-north-africa

14. Mara Karlin and Tamara Cofman Wittes, 2019, “America’s Middle East Purgatory: The Case for Doing Less”, Foreign Affairs

15. For similar operational postures, see “U.S. to Maintain Robust Over-the-Horizon Capability for Afghanistan if Needed”, available at https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2682472/us-to-maintain-robust-over-the-horizon-capability-for-afghanistan-if-needed/; and “Ayman al-Zawahiri’s killing and the US’ ‘over-the-horizon’ counterterrorism capability”, available at https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/ayman-al-zawahiris-killing-and-the-us-over-the-horizon/

16. Anthony H. Cordesman and Nicholas Harrington, “The Arab Gulf States and Iran: Military Spending, Modernization, and the Shifting Military Balance,” Center for Strategic and International Studies Working Paper, December 2018,

17. “Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country”, Defense Manpower Data Center, September 1998 and September 2008

18. Thorough breakdown details in the dataset of the Costs of War project, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, available at https://www.brown.edu/news/2021-09-01/costsofwar

19. See, Justin Logan, 2010, “The Structure of Domestic Politics: Assessing the Obstacles to a Grand Strategy of Restraint” APSA 2010 Annual Meeting Paper; and, Nuno P. Monteiro, 2012, “Unrest Assured: Why Unipolarity Is Not Peaceful” International Security

20. See, Douglas Brinkley, 1997, “Democratic Enlargement: The Clinton Doctrine”, Foreign Policy; George W. Bush, 2001 “Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People United States Capitol” Washington, D.C.; and Stephen M. Walt “Obama Was Not a Realist President”, 2016, Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center.

21. See, Raymond Stock, 2011, “The Islamist Spring: What Mubarak Got Right, What Obama Got Wrong”, FPRI; Sumantra Maitra, 2016, “Before We Head to Libya Again”, War on the Rocks; and Patrick Porter, 2018, “Why America’s Grand Strategy Has Not Changed: Power, Habit, and the U.S. Foreign Policy Establishment,” International Security

22. For current force strategy in the Middle East, see “Posture Statement of General Kenneth F. McKenzie, Jr., Commander, United States Central Command,” Statement before the House Armed Services Committee, March 10, 2020.

23. US CentCom Bomber Task Force mission to Middle East, March 2021