Primer: Impeaching Judge James E. Boasberg for Judicial Abuse

Introduction

The judicial branch does not have immunity from accountability. Article III’s promise of life tenure is a conditional trust rooted in the requirement of “good Behaviour.”1 When a federal judge violates that standard through systemic abuse of power, overt political bias, or willful disregard of constitutional structure, impeachment is the suggested constitutional remedy.2

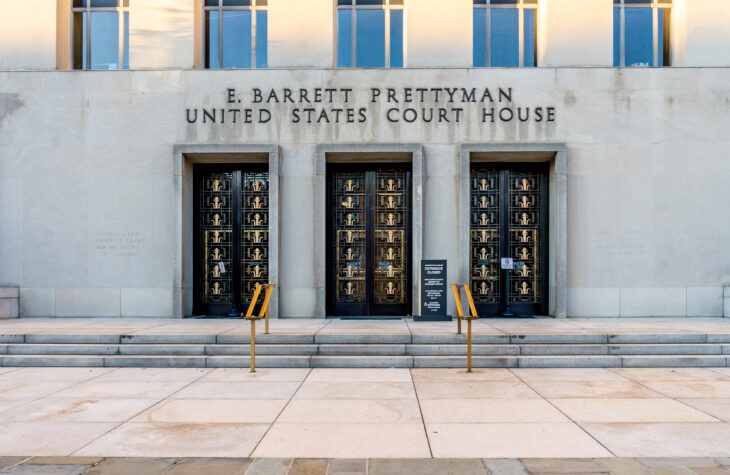

Judge James E. Boasberg is an Obama appointee to the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. His conduct, ranging from unauthorized nationwide injunctions to interference with deportation operations and surveillance of U.S. senators, has provoked alarm and underscored the threat posed by radical jurists untethered to the constitutional order. As shown by a formal misconduct complaint submitted by senior DOJ officials and an impeachment resolution pending in the House of Representatives, Boasberg’s actions implicate not only the credibility of the bench but also the rule of law itself.3 The House of Representatives, and ultimately the Senate, must consider whether Boasberg’s conduct meets the constitutional standard for impeachment.4

Perhaps equally critical is understanding the full scope of the institutional capture of the courts by progressive radicals. This will require, at a minimum, intentional examination of such activists before the House of Representatives. It is time for Congress to exert its oversight powers and bring judges like Boasberg before the relevant committees to answer questions and explain themselves before the American people.

I. The Framework for Judicial Impeachment

A. The Constitutional Standard

Under Article II, Section 4, all “civil Officers of the United States” are subject to impeachment for “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”5 The phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” is not confined to violations of the criminal code. It includes abuses of official power, corruption, breaches of the public trust, and conduct incompatible with the duties of office.6 As Blackstone observed, “The first and principal [high misdemeanor] is the mal-administration of such high officers, as are in public trust and employment. This is usually punished by the method of parliamentary impeachment.”7 The standard for judges is especially clear. Article III, Section 1 conditions judicial tenure on “good Behaviour,” a phrase borrowed from English common law and understood at the Founding to denote not criminality but fitness for office.8

B. Judicial Impeachment in Practice

Historical practice confirms that impeachment of federal judges is neither extraordinary nor confined to cases of criminal conviction. From the early republic to today, Congress has repeatedly used impeachment to address judicial misconduct, abuse of authority, and conduct incompatible with the constitutional requirement of good behavior. The House has impeached fifteen federal judges, and eight have been convicted and removed by the Senate.9 These eight federal judges are the only individuals ever convicted by the Senate in impeachment, showing that the threshold for judicial impeachment, breaking the good-behavior standard, is not a constitutionally impossible one.10

The first federal judge ever impeached, John Pickering, was removed not for criminal acts but for mental instability, intoxication on the bench, and inability to discharge judicial duties, demonstrating that impeachment reaches fitness for office rather than criminality alone.11 His removal in 1804 established that good behavior is an enforceable constitutional standard.

Similarly, Justice Samuel Chase was impeached for arbitrary and oppressive conduct, including political bias and abuse of judicial authority.12 Although the Senate ultimately acquitted Chase, the case is critical: It confirms that impeachment may properly be based on judicial misconduct and abuse of power, even when the Senate exercises restraint at the conviction stage.13 The Chase impeachment set boundaries and not immunity.

Congress has repeatedly returned to impeachment when judges have abused contempt powers or used judicial authority to punish critics or control political outcomes.14 Judge James H. Peck was impeached for abuse of the contempt power.15 Though Peck was acquitted in the Senate, Congress made clear that abuse of judicial power falls within impeachment’s scope.16

Other impeachments reinforce the same principle. Charles Swayne and George W. English were impeached for abuse of office and misuse of authority. Robert W. Archbald was removed for improper relationships with litigants, underscoring that conduct undermining judicial impartiality is incompatible with good behavior.17 Halsted Ritter was convicted and removed for favoritism and ethical misconduct.18

In the modern era, impeachment has continued to serve as a check on judges who refuse to conform their conduct to constitutional norms. Harry Claiborne, Alcee Hastings, and Walter Nixon were removed after criminal convictions.19 Most recently, G. Thomas Porteous was removed in 2010 for corruption and making false statements, reaffirming that impeachment remains a living constitutional mechanism.20

Mark W. Delahay, George W. English, and Samuel B. Kent all resigned under the weight of impeachment, confirming its disciplinary force.21 The consistent theme is not partisanship or criminality but a misuse of judicial power, an erosion of impartiality, and conduct incompatible with the judiciary’s constitutional role.

This historical record directly contradicts any claim that Boasberg’s conduct is insulated by judicial independence or novelty. Judges have been impeached for far less systemic interference with executive authority than Boasberg’s repeated issuance of nationwide injunctions, assertion of authority after Supreme Court reversal, and use of contempt threats against executive officials. History shows that impeachment exists precisely for judges who cease to act as neutral arbiters and instead act as rogue adjudicators.

II. The Case Against Judge Boasberg: Pattern of Judicial Tyranny

The formal complaint against Boasberg and its associated filings present a pattern of behavior that, viewed collectively, constitutes clear impeachable misconduct. Further, the actions by Boasberg are so uniquely indefensible that Congress should subpoena him to testify before the House Committee on the Judiciary as part of a broader effort to unveil the institutional capture of courts by progressive radicals.

A. Judicial Prejudice and Canon Violations

At the March 11, 2025, Judicial Conference, Boasberg warned fellow judges and the chief justice that President Donald Trump would “disregard rulings of federal courts,” predicting a “constitutional crisis.”22 These remarks, made while cases involving the Trump administration were pending before him, violated Canons 1, 2(A), and 3(A)(6) of the Code of Conduct for U.S. Judges, which call for judges to uphold integrity, to be impartial, and not to make public comments on impending litigation.23 Boasberg’s extrajudicial statements show prejudgment, violate impartiality, and undermine judicial neutrality. His actions provide further evidence of his intentions to wield his bench as a weapon against his political enemies.

B. The J.G.G. v. Trump TRO: Nationwide Injunction Without Process

Just four days after the conference, Boasberg issued a temporary restraining order (TRO) halting the removal of several individuals affiliated with Tren de Aragua, a designated transnational criminal organization.24 But rather than confining relief to the named plaintiffs or to the District of Columbia, Boasberg’s order functionally extended its reach nationwide, forbidding federal immigration authorities from removing any individual of similar status, regardless of location, legal posture, or connection to the plaintiffs. The Supreme Court summarily vacated the injunction less than a month later.25

As Center for Renewing America (CRA) Fellow Ken Cuccinelli has shown, the misuse of nationwide injunctions by district courts has become a tool for rogue judges and lawless judicial control.26 Boasberg’s conduct perfectly exemplifies this abuse, bypassing the normal adjudicative process and substituting personal judgment for legislative and executive authority.

C. Boasberg’s Overreach After Supreme Court Reversal

After the Supreme Court vacated Boasberg’s TRO on April 1, 2025, effectively allowing the federal government to resume deportations, Boasberg issued a forty-six-page memorandum opinion accusing federal officials of criminal contempt.27 He claimed that the officials had violated his order before the Supreme Court’s ruling was formally entered, even though the justices had already announced their decision.28 In doing so, Boasberg asserted that his own order remained enforceable for several days after the Supreme Court had effectively nullified it.29 The result was a threat of criminal sanctions against executive officials for actions that aligned with the Supreme Court’s decision.30 This unusual and aggressive step gave the appearance that Boasberg was punishing federal officers for following the Constitution’s hierarchy of authority, where the Supreme Court and not a district judge has the final word.

Such threats are unprecedented. They expose an authoritarian judicial posture where a single judge attempts to override the constitutional structures of Article II and Article III.

D. National Security Disruption

The J.G.G. v. Trump order disrupted deportation flights in midair, requiring immediate course reversal of aircraft en route to El Salvador.31 The individuals were being expelled under the Alien Enemies Act for credible threats to national security.32 Boasberg’s interference risked diplomatic relations, intelligence operations, and airspace safety.33 The Alien Enemies Act grants the president sole and unreviewable discretion to invoke its provisions, including the authority to decide if an invasion has occurred.34 As the Supreme Court has noted, for a court to question the president’s determination under the act would be to assume a role intended for the political branches of government.35 The court has emphasized that it is not within the judiciary’s purview to challenge the president’s decisions under the Alien Enemies Act because such matters involve political judgments for which judges lack both technical expertise and official responsibility.36 As the House lays out in its impeachment articles, this breach of constitutional duty was a major breach of the separation of powers.37

E. Operation Arctic Frost

In perhaps the most chilling example of judicial tyranny to date, Boasberg authorized covert surveillance orders as part of an authoritarian Biden-era DOJ operation known as Arctic Frost, which targeted members of Congress without any legal notification, as required under 2 U.S.C. § 6628.38 This statute mandates that when federal law enforcement seeks to surveil members of Congress, it must notify the affected individuals, ensuring that Congress is aware when its members are being monitored.39 Boasberg’s approval of these orders not only bypassed this crucial safeguard but also demonstrated a disturbing disregard for the principle of legislative immunity that underpins the separation of powers. Indeed, according to Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX), Boasberg’s court order strictly prohibited AT&T from informing Cruz that he was being surveilled for a full year because “the court finds reasonable grounds to believe that such disclosure will result in destruction of or tampering with evidence, intimidation of potential witnesses, and serious jeopardy to the investigation.”40

The absence of notice to Congress raises serious questions about whether Boasberg’s actions were the result of gross negligence or, more troubling, intentional evasion of statutory protections designed to preserve congressional independence. Even more alarming is the scope of Arctic Frost. This witch hunt targeted more than 430 organizations and individuals on the political right, including private citizens, in politically motivated prosecutions designed to decimate and imprison the radical left’s opposition. That Boasberg so willingly complied with the Biden DOJ’s Arctic Frost abuses against sitting senators and private citizens suggests that he believes not only that he is above the law but that he is the law.

III. Judicial Independence and the Absence of Immunity from Impeachment

Defenders of Boasberg will invoke judicial independence and judicial immunity as barriers to impeachment. Federalist No. 78 rejects both arguments. Alexander Hamilton’s defense of judicial independence was neither a grant of supremacy nor a promise of personal insulation.41 It was a conditional doctrine, rooted in the judiciary’s institutional weakness and its obligation to exercise judgment, not will.42 Hamilton described the judiciary as “beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power,” possessing “neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment.”43 Judicial independence was justified to protect judges from political retaliation while they faithfully applied the law, not to shield judges who exceeded constitutional limits. Life tenure during good behavior was designed to secure impartiality, not to authorize judicial governance.44

Critically, judicial independence is inseparable from the good-behavior requirement. Independence exists to preserve constitutional adjudication, not to license defiance of constitutional structure. When a judge substitutes personal policy preferences for constitutional boundaries, he forfeits the justification for independence Hamilton articulated. At that point, the Constitution does not protect him but subjects him to accountability, and in this case, that is impeachment.45

Judicial immunity does not alter this conclusion. Judicial immunity is a narrow common-law doctrine that protects judges from civil damages for judicial acts taken within jurisdiction.46 It does not apply to impeachment, congressional investigation, or removal from office. Impeachment is not a civil proceeding; it is a constitutional mechanism designed precisely to address abuses of office that immunity doctrines cannot reach.47

Nothing in Federalist No. 78 suggests that judges are immune from removal. To the contrary, Hamilton assumed impeachment as an essential safeguard against judicial misconduct.48 Independence without enforcement of the good-behavior standard would invert the constitutional design, transforming independence into impunity, which is an outcome the Founders explicitly rejected.

Federalist No. 78 also forecloses claims of judicial supremacy. Hamilton made clear that judicial review does not render courts superior to the political branches.49 Courts are subordinate to the Constitution itself and serve as intermediaries between the people and their representatives.50 Their role is to prefer the Constitution to statutes when the two conflict and not to override executive discretion in areas committed to the political branches, nor to govern national policy through equitable decrees.51

Boasberg’s conduct departs sharply from this constitutional model. By issuing functionally nationwide injunctions untethered to parties before the court, interfering with executive deportation operations, asserting continuing authority after Supreme Court reversal, and threatening criminal contempt against executive officials for complying with higher law, Boasberg exercised will rather than judgment. Such conduct represents not independence but usurpation that meets the threshold of impeachment.

Under Hamilton’s framework, this behavior lies outside the protections of judicial independence and immunity. Judicial immunity cannot shield a judge from impeachment any more than legislative privilege can shield a legislator from expulsion. The Constitution provides impeachment precisely because independence alone cannot serve as a check on abuse.

IV. Alternatives Should Congress Fail to Impeach Boasberg

Should the House fail to impeach Boasberg, there is a series of actions the legislative and executive branches could take to limit the “judicial tyranny” of rogue judges like Boasberg.52 For the purposes of this paper and for brevity, those remedies will not be listed in detail here. The solutions outlined by CRA align with the Founders’ understanding of the judiciary: a branch of government that exercises judicial review, not judicial supremacy.53 As established in Marbury v. Madison, judicial review does not empower judges to become political agents or dictate national policy.54 Rather, it ensures that laws are interpreted in light of the Constitution. Boasberg’s actions reflect a dangerous shift toward judicial supremacy, which CRA’s proposed reforms seek to correct, reaffirming the need for balance between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

However, it is incumbent on elected members of Congress to exert their constitutional oversight powers against a judge so clearly at war with the very contours of the republic. At a minimum, the House should subpoena Boasberg to testify on his abuses and attempt to defend his actions in the light of day instead of hiding behind a black robe and a gavel. This must be part of a larger effort to expose the full scope and extent of the radical left’s capture of the courts and the degree to which our judicial system has been compromised.

V. Conclusion: A Call to Restore Constitutional Balance

Boasberg’s repeated abuses of judicial power represent a direct assault on the constitutional separation of powers. His actions not only subvert the executive’s constitutional prerogatives but also undermine the judicial independence that was meant to protect the system of checks and balances. Instead of serving as a neutral arbiter of the law, Boasberg has used his position to wage an ideological war on the American people and their elected representatives, bypassing both congressional intent and the authority of the president. Such judicial behavior is not only incompatible with the good-behaviour standard outlined in Article III but also poses a grave threat to the integrity of our republic.

Impeachment is a constitutional remedy for a federal judge who acts in violation of the standard of good behavior and undermines the constitutional structure. In this instance, impeachment is not only warranted but necessary to restore balance and uphold the integrity of the judiciary. Congress must not remain passive and should not only vote on impeachment but also force Boasberg to testify before the House Judiciary Committee under oath.

Further, as the articles of impeachment go through the House, the DOJ should follow through with seeking the relief requested in its complaint against Boasberg: that the Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia refer the complaint to a special investigative committee under Rule 11(f); order interim corrective measures such as reassigning all J.G.G. v. Trump and related cases to another judge; and, pending committee review, impose the appropriate disciplinary actions related to willful misconduct.55

Congress can act to reassert control and ensure that judges like Boasberg do not continue to overstep their bounds. The rule of law cannot stand if federal judges are allowed to unilaterally dictate national policy and wage war on American voters and citizens under the belief that a lifetime appointment grants them immunity from the consequences. The American people must be able to rely on their elected representatives to restore balance to the government or risk surrendering the republic to tyranny by tribunal. It is time to act, for the health of the Constitution, the security of the nation, and the preservation of the republic.

Endnotes

1. U.S. CONST. art. III, § 1.

2. Id. art. II, § 4.

3. Complaint of the United States Department of Justice Against Chief Judge James E. Boasberg (July 28, 2025), https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/FINAL-Misconduct-Complaint-7.28.pdf; H. Res. 229, 119th Cong. (2025).

4. Id.

5. U.S. CONST. art. II, § 4.

6. The Federalist No. 65 (Alexander Hamilton) (Mar. 7, 1788).

7. 4 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England *121 (1769).

8. See Saikrishna Prakash & Steven D. Smith, How to Remove a Federal Judge, 116 Yale L.J. 72, 78 (2006).

9. Jared Cole & Todd Garvey, Impeachment and the Constitution, CONG. RSCH. SERV. (Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46013.

10. Id.

11. See Federal Judicial Center, Impeachments of Federal Judges, https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/impeachments-federal-judges (last visited January 7, 2026).

12. Id.

13. Id.

14. Id.

15. Id.

16. Id.

17. Id.

18. Id.

19. Id.

20. Id.

21. Id.

22. Complaint of the United States Department of Justice Against Chief Judge James E. Boasberg (July 28, 2025), https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/FINAL-Misconduct-Complaint-7.28.pdf; H. Res. 229, 119th Cong. (2025).

23. Id.

24. Minute Order, J.G.G. v. Trump, No. 1:25-cv-766 (D.D.C. Mar. 15, 2025).

25. Trump v. J.G.G., 604 U.S. ___ (2025).

26. See Ken Cuccinelli supra note 4.

27. Mem. Op., J.G.G. v. Trump, No. 1:25-cv-766 (JEB), (D.D.C. Apr. 16, 2025).

28. Id.

29. Id.

30. Id.

31. See Mike Davis, MIKE DAVIS: Why D.C.’s Trump-Hating Judge Boasberg Must Be Impeached, FOX NEWS (Dec. 13, 2025), https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/mike-davis-why-dcs-trump-hating-judge-boasberg-must-impeached.

32. Id.

33. Id.; see also Complaint of the United States Department of Justice Against Chief Judge James E. Boasberg (July 28, 2025), https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/FINAL-Misconduct-Complaint-7.28.pdf; H. Res. 229, 119th Cong. (2025).

34. 50 U.S.C. § 21.

35. Ludecke v. Watkins, 335 U.S. 160 (1948).

36. Id.

37. H. Res. 229, 119th Cong. (2025).

38. Sen. Charles E. Grassley, Sen. Ron Johnson & Rep. Jim Jordan, Letter to the Honorable James E. Boasberg, Chief Judge, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (Nov. 20, 2025), https://www.grassley.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/grassley_johnson_jordan_to_boasberg_-_nondisclosure_orders.pdf; see also 2 U.S.C. § 6628.

39. 2 U.S.C. § 6628.

40. Sen. Ted Cruz, Boasberg Is a Radical Leftist:’ Cruz Torches Biden Judge, Calls for Impeachment Over GOP Subpoenas (Oct. 30, 2025), The Economic Times, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FaQZz5ugosg.

41. The Federalist No. 78 (Alexander Hamilton) (May 28, 1788).

42. Id.

43. Id.

44. Id.; U.S. CONST. art. II, § 4.

45. Id.

46. See Bradley v. Fisher, 80 U.S. (13 Wall.) 335, 347 (1872).

47. U.S. CONST. art. II, § 4.

48. See The Federalist No. 78 (Alexander Hamilton) (May 28, 1788).

49. Id.

50. Id.

51. Id.; Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 177–78 (1803).

52. See Ken Cuccinelli, Policy Brief: The Threat of Judicial Tyranny Is Far from Over, CTR. FOR RENEWING AM. (July 29, 2025), https://americarenewing.com/issues/policy-brief-the-threat-of-judicial-tyranny-is-far-from-over/.

53. Id.

54. 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803).

55. Complaint of the United States Department of Justice Against Chief Judge James E. Boasberg (July 28, 2025), https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/FINAL-Misconduct-Complaint-7.28.pdf.