Policy Brief: Pivoting the US Away from Europe to a Dormant NATO

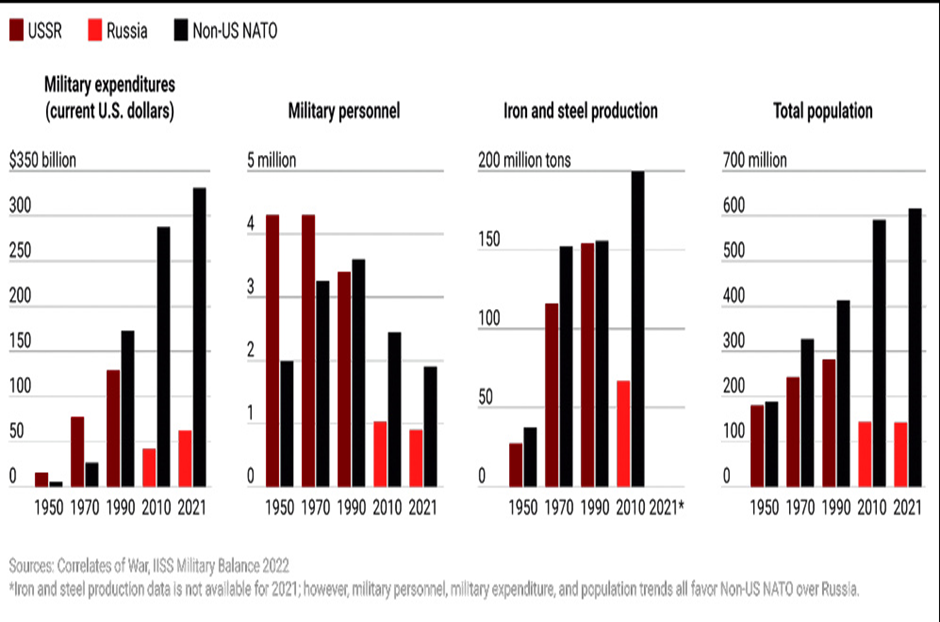

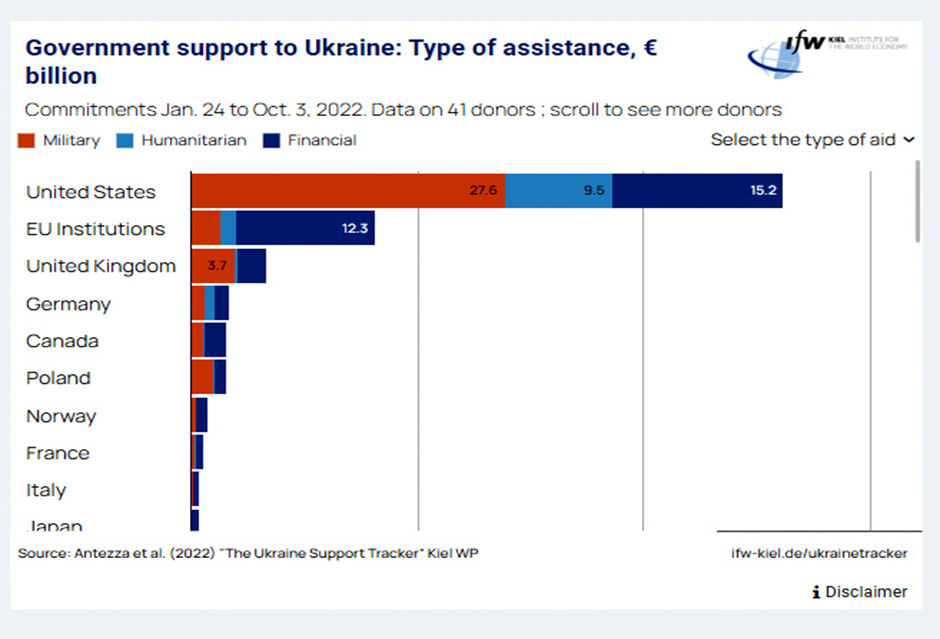

As Russia’s Ukrainian invasion grinds into a second year, a few key developments are taking place. China is building up its nuclear warheads stockpile, likely aiming to be a nuclear peer rival to the US by 2035.1 Europe has accused the US of mercantilism and cynically exploiting the war for profit while simultaneously demanding more American engagement to subsidize its defense.2 The latest bipartisan omnibus bill’s inclusion of another $45 billion in support of Ukraine confirms the cost of the Ukraine war is now a continuing drain on the American budget, and the US continues to outspend Europe for a war that is essentially in its backyard.3 This is in spite of the fact that Russia has, by most reasonable metrics, ceased to be a hegemonic challenge in Europe.4 With the challenges of a rising China and a diminished Russian threat to Europe, it is high time for the United States to pivot away from the continent as a national security priority.

This policy brief explores what an American grand strategy in Europe should prioritize. The paper highlights the history of the debate about NATO commitments, outlines Washington’s current strategy of forward presence, and argues why that is flawed under the changed circumstances. The paper concludes with an alternative policy of a “dormant NATO,” wherein Europe is the primary security provider of the European front and flanks. At the same time, the US is an “offshore balancer,” focused loosely on global maritime and trade security and the Asia-Pacific theater.

American overcommitment to NATO is a case of ideology over interest.

After the Second World War, Britain and France could not balance the threat of an expansionist great power like the Soviet Union. The threat of Moscow occupying or influencing the entirety of the European continent was a significant challenge to American grand strategy. Europe was decimated, and the Soviet Union was, in terms of production capacity and manpower, the largest battle-ready military force in 1949 and had de-facto control over half of Europe. If the US had not challenged Soviet hegemony over the then most crucial continent, then it risked the Soviet Union becoming the strongest superpower in history and the spread of communism globally, a direct threat to the American way of life. The balancing of the USSR’s expansionist ambition via NATO was, therefore, not just a moral but a political, economic, and strategic necessity.

The end of the Cold War and the diminishing Russian strategic threat resulted in a significant reduction of American forces in Europe but did not decrease European dependence on the US. Subsequent American grand strategy ensured that Europe remained incentivized to avoid carrying the burden of their own defense. Nowhere was this atrophy more prominent than in Western Europe, particularly in Germany, which in 1989 could field around twelve divisions alone.

The post-Cold War NATO expansion was – despite repeated assertions to the contrary – pushed by Europeans first and then by the Clinton Administration.5 The initial push was from the Central European countries of Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, rightly worried about Russian revanchism. But the strongest push for NATO expansion came from Germany, under German defense minister Volker Rühe.6 Ultimately, however, the Clinton Administration was committed to expanding NATO and promoting democratic peace.7 In January 1994, Bill Clinton stated in Prague that “the question is no longer whether NATO will take on new members, but when and how.”8 Clinton National Security Council (NSC) speechwriter Jeremy Rosner led the NATO Enlargement Ratification Office and alongside future Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, lobbied for Senate Approval of NATO’s geographic expansion, calling it “enlargement” as opposed to a more aggressive sounding “expansion.”

During the mid-nineties, there were still glimpses of a prudential opposition to an unchecked expansion of military commitment, and even the Pentagon was initially opposed to it.9 Notably, Strobe Talbott, then adviser to the Secretary of State, cautioned, “the key principle, as I see it, is this … An expanded NATO that excludes Russia will not serve to contain Russia’s retrograde, expansionist impulses; quite the contrary, it will further provoke them.” Within the foreign policy establishment, there was clear opposition to continuous NATO expansion, a sign of narrow realism in an era when moralistic commitments were still subservient to the national interest. George F. Kennan, for example, said in February 1997 that it was the “most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold-War era.”

Nevertheless, the unipolarity and the purported “end of history” proved politically intoxicating. Added to that was a flawed worldview that justified institutionalizing peace by creating supra-national bureaucracies and expanding NATO (primarily a defensive alliance) in the name of democracy promotion. The result was a strategic posture that atrophied local allies and begot sanctimonious protectorates entwined to their tribal and ethnic grievances. Like the Foederati and Rome, these protectorates were often more zealous and crusading than the hegemon itself and saw the hegemon as a means to achieve their security ends. For example, every national security strategy document of the Baltic states, from the late nineties to the present, argues for firmly tying the United States to the security of Eastern Europe and the survival of those states. In short, European interests were, and continue to be, primarily European.

NATO’s current posture and flawed strategy.

In June 2022, just a few months after Russia invaded Ukraine, NATO released a strategy document that, for the first time, named China a strategic threat. That coincided with Chinese military exercises and then Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan.10 The document stated that “the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values. The PRC employs a broad range of political, economic and military tools to increase its global footprint and project power, while remaining opaque about its strategy, intentions and military build-up. The PRC’s malicious hybrid and cyber operations and its confrontational rhetoric and disinformation target Allies and harm Alliance security.”

The document outlined the core task of NATO as “deterrence and defense; crisis prevention and management; and cooperative security; NATO’s nuclear capability is to preserve peace, prevent coercion and deter aggression.”

Yet the rest of the strategy document veered towards incoherence, stating that the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a fundamental violation of norms and principles of a stable European order and that “Moscow’s behavior reflects a pattern of Russian aggressive actions against its neighbors and the wider transatlantic community.”

If threat is will plus capability, then there is no evidence thus far to indicate that Russia either has the will or capability to launch an expansionist push into the rest of Europe, given their performance so far in Eastern Ukraine. While the invasion violates a feeble norm against state versus state war over territory, it is not clear why a peripheral war in the far eastern reaches of Europe would affect core American strategic interests.

The document further stated that the alliance faces “persistent threat(s) of terrorism, in all its forms and manifestations. Pervasive instability, rising strategic competition, and advancing authoritarianism challenge the Alliance’s interests and values.” However, NATO was not meant to deter non-state actors, and most European terrorism comes either from elements already living within the European Union or from unchecked migration from Africa, issues which NATO is both structurally ill-qualified and legally unsuitable for countering. Furthermore, NATO’s assertion that “advancing authoritarianism” is a threat to the alliance raises some major questions. Who gets to define what “authoritarianism” is? In an era where any deviation from politically liberal internationalism is considered authoritarian by some, is the alliance now interested in policing within its borders against its own citizens for the threat of authoritarianism, and if so, what measures is it willing to take to tackle this vaguely defined threat?

Finally, NATO argues that climate change is a defining threat of our times, as a crisis and threat multiplier, because it enhances instability.

In short, the many concerns listed have no clear tie to NATO’s mission of “deterrence and defense.” Instead, NATO is an alliance in need of an adversary, and like every bureaucratic organization, it is preoccupied with its own growth and sustenance. Since the second phase of expansion began, the alliance membership continued to grow and currently stands at around 30, compared to the Cold War peak of 16 member states.

The immediate result of NATO expansion has been the decline in capabilities of the Western European states, who do not foresee (rightly) any major strategic or hegemonic threat rising in the East. Russia is a shadow of its former self, and even though it has captured bits and pieces of Ukraine, the misadventure has come with a crippling cost. Russia is unlikely to be a continental threat anytime soon. American manpower and logistics, on the other hand, guard the Eastern states. Most Eastern states, especially the Baltics, oppose any form of European autonomy precisely because they see NATO as the ultimate guarantor of their sovereignty and bureaucratic protection against the US turning too narrowly nationalistic.11 Like other bureaucratic organizations, NATO has increasingly focused on out-of-area operations, including Afghanistan and Libya.

The US has struggled to coerce European allies into spending more for their own defense, and every effort to give an ultimatum or timeline for burden shifting to Europe has been thwarted by lobbying from either the Europeans or American Trans-Atlanticists. It is also imprudent to expect that NATO would take on any adequate burden regarding China. The European public is averse to a conflict with China. And in a recent report in the Financial Times, for example, a European military strategist said that “the most important implication for Nato of a potential conflict in the Taiwan Strait is the likely need for European militaries to backfill US military assets in the north Atlantic in the event that the US has to redeploy some assets to the Indo-Pacific. Nato is unlikely to get involved directly into a Taiwan crisis or war.”12

The Euro-American capability gap.

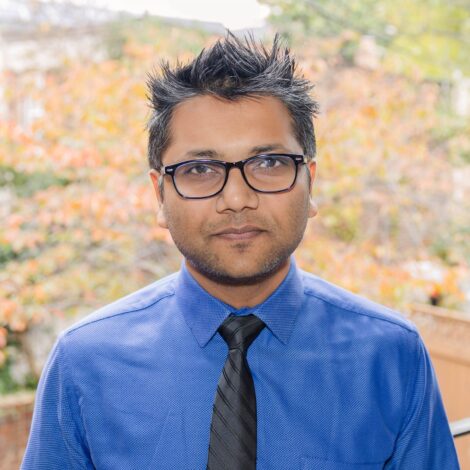

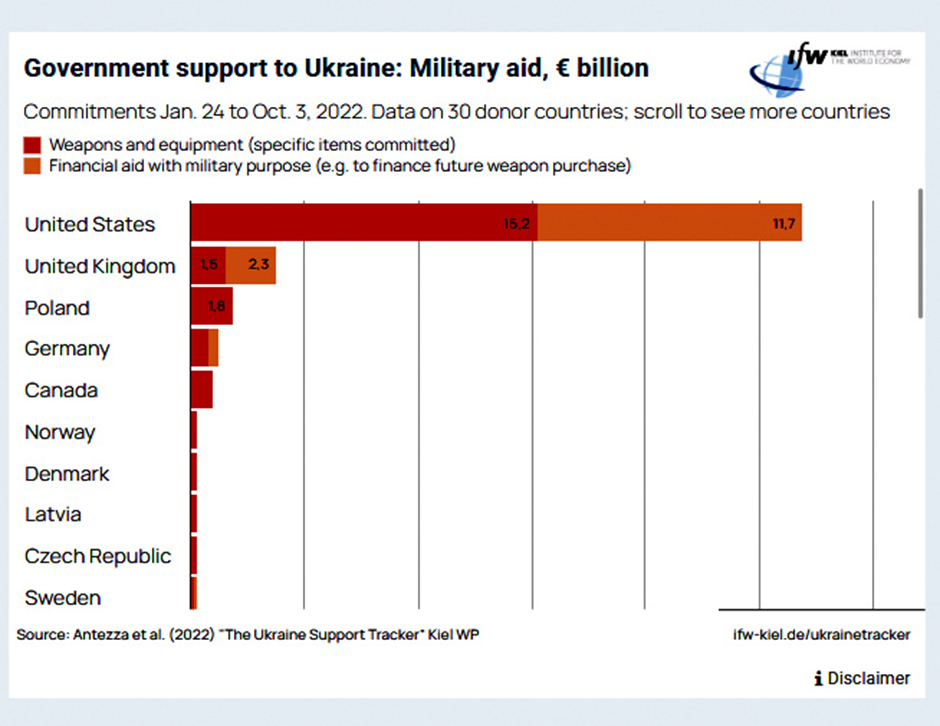

As indicated in the below graphics, the difference in aggregate power between the EU, NATO, and Russia overwhelmingly favors Europe. American contributions to Europe, compared to Europeans themselves, suggests the US is being fleeced.13

The charts above support three specific assessments. First, the United States dwarfs Europe in relative contribution and aid to Ukraine. While it is understandable that the US, as the hegemon, is determined to share more of the burden, it is not clear why Europe, on the whole, is not on an equal footing when it comes to providing aid. Second, because geography dictates interests, there will never be a Western European push for more burden sharing as long as American muscle, money, and manpower guard their Eastern frontier. Third, Europe can defend itself and dwarfs Russian capabilities. Partially, their revealed preferences indicate that Western Europe does not see a Russian strategic threat and sees an armed Eastern Europe as a buffer between it and Russia. As long as American power is beefing up those regions, there is no need for Western Europe to do more.

A final point reflects the different interests within NATO. The Eastern European powers are more interested in America bearing their security burden and NATO expansion. Meanwhile, the Western European powers are interested in a finite NATO boundary and free-riding on America. The current US posture is, therefore, unsustainable.

Toward a Dormant NATO.

Previous CRA briefs argued that the US needs a new European grand strategy for the emergence of a natural equilibrium in Europe to encourage the rise of European natural balancers and a finite NATO bloc with no further expansion.14 This brief argues for a complementary strategy of a Dormant NATO framework consisting of two major pillars. The first pillar is significant retrenchment and burden shifting in Europe, with a pledge towards a finite NATO border and no further territorial expansion. The second pillar is facilitating a framework for European manpower to be the primary defense of Europe’s frontiers, with America as a balancer of last resort instead of a perpetual American forward presence.

As noted above, NATO expansion was an ideological decision during the peak-post-Cold-War unipolarity and was bound to be unsustainable in the long run. Like most bureaucracies, the supranational organization grew to survive. It morphed from a military alliance to an ideological and political group, simultaneously finding new tasks to sustain its existence while undermining the nationalist or independent strategic thinking of its member states. Finally, the expansion of NATO has stymied European burden-sharing in two main ways. It resulted in perpetual free-riding for the Western powers, who saw no threat on their horizon. It also resulted in a number of Eastern protectorates, unsustainably dependent on foreign great powers for survival. Yet they are often ideologically liberal internationalists, extremely sanctimonious, and partial to taking sides in the domestic debates of their foreign great power benefactors.

In this context, it is essential to remember that burden shifting in Europe is more manageable than compelled burden sharing. Burden sharing is a collaborative process that risks derailment by the entrenched regional protectorates in Europe and the NATO bureaucracy. Burden shifting is a unilateral exercise of power driven by American interests. It provides a rapid and firm timeline, forcing Europe to plan resources and alternatives. Europe faces no comparable threat to the one it faced during the Cold War, and European combined capabilities far outweigh Russia’s. It is in the European interest to defend finite European frontiers.

The Framework for a Dormant NATO:

Timeframe for US burden shifting.

The US should start orienting a fixed timeline of burden shifting within NATO and undertake a more detached “offshore balancing” approach.

An offshore balancer strategy entails the US serving as a logistics provider of last resort and Washington as the final guarantor of free sea lanes and trade routes. It would mean a limited American naval and air presence in Europe to support these missions. Additionally, since Britain and France are historical allies with independent nuclear deterrents, it is in America’s interest to maintain closer security relations with these nations than the rest of Europe. A dormant NATO would mean that all other structures and local defense costs would burden the Europeans.

For example, America had to offset ammunition losses during NATO missions in Libya in 2011 for the same reason the US is still out-producing and out-supplying NATO and the EU countries in Ukraine. It is not a capability gap but a deliberate European strategy of free-riding. Europeans will never take their burden seriously until the US is not there to break the glass in case of a sudden fire.

It is, therefore, in the interest of the Europeans to not only scale up their munitions production but also maintain uniformity with American arms. This will enable the United States to be an effective logistics provider of last resort and to maintain an opportunity for Europe to purchase arms and munitions from American producers.

The NATO bureaucracy is a barrier in the path of reduced American commitment. It is self-sustaining and prone to push missions that are beyond NATO’s core role and, at times, opposed to the domestic interests of the United States. Radically reducing the NATO bureaucracy should be a chief aim.

The US is the largest funder of NATO by virtue of having the largest GNP. The fund is usually divided into the civil budget, military budget, and investment. There are currently over a thousand civilian international staff within NATO, and the alliance routinely founds nonprofit institutions in member countries that aim to maintain support for NATO membership. NATO bureaucrats regularly opine on political issues, either about adversaries or about the domestic policies of allied nations. The US – specifically the US Congress through the appropriations process – should stop funding all this political grand-standing which often undermines America’s national interest.

A dormant NATO would mean a complete moratorium on activities that do not fall within a strictly military remit and only maintain organizational structures that would be needed and activated in the case of a major war.

NATO should also stop all expansion. A bloc that is constantly mutating and expanding cannot have a coherent grand strategy. NATO does not serve the overall defense of the bloc. It undermines national interest (even mild forms of benevolent nationalism and prioritization of member states), especially in the hegemon, by an ever-expanding self-sustaining Soviet-lite bureaucracy and foreign lobby groups. It encourages protectorates to influence the domestic and foreign policy of great powers. It results in freeriding and strategic chaos. NATO’s morphing from a defense alliance into an ideological bureaucracy needs urgent reversing, and a finite border for the bloc is the primary prerequisite.

Eventually, the likely creation of mini-ententes between various local powers and balancers may eliminate the need for a NATO-like transatlantic alliance altogether. Accordingly, the United States government should never take a full withdrawal from NATO off the table. Policymakers should also be prepared to exercise this option – especially if NATO’s European members do not take substantial moves to achieve a burden shift.

Europeans guarding the European frontier.

European powers are more than capable of guarding Europe’s frontiers. NATO’s rapid response force is on track to expand. Still, it would be prudent to man the force purely with European infantry and logistics under a European command within NATO.

NATO should immediately forego out-of-area operations, and the European members of NATO should be guarding European frontiers and landmasses. Germany or the Netherlands sending occasional frigates to the Pacific in no way enhances Asian security nor indicates a smarter burden sharing. European frigates on patrol in the Baltic Sea are a better utilization of scant resources.

The Scandinavian countries are more than capable of providing Arctic security, Signals intelligence (SIGINT), as well as patrolling the Bering, Mediterranean, and Baltic seas. The Swedish navy’s sub-surface capabilities are among the premier in their class in the world. France and Greece are already inking defense management of the Mediterranean under their bilateral defense pact. Similarly, there are Polish-British security arrangements and talks of the German army permanently stationed in Lithuania. While premature, these provide opportunities for the United States to partially retrench.

Following the degradation of Russian conventional forces, there is no need for the United States to deploy any armored infantry or combat support units to Eastern Europe. All infantry brigades and logistics permanently deployed in East Europe should be European in combination and command. Poland is on its way to being the largest European NATO force after Turkey. At the same time, Finland has large infantry reserves, and Germany can resume its Cold War-era role as NATO’s armored backbone.

Conclusion

No great power in history has simultaneously embarked on a rapid build-up of both offensive capabilities – in this instance, China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) – and their deterrence capabilities, in this instance, China’s nuclear warheads; so, it is reasonable to expect that they are planning for a war. One might disagree on the strategy to either contain China or buck pass the security burden, but not considering China as a grand-strategic challenge that needs some prioritization of resources is a strategic failure in planning. The American intelligence reports also conclude that Beijing, for all practical purposes, is preparing for some sort of conflict in the next couple of decades or so. Prioritization of strategic theatres is the key to a grand strategy and inevitably leads to trade-offs.

There are two logical ways to offset the China threat. First, a Euro-Atlantic pivot to Asia with NATO patrolling the Pacific; and second, a relatively self-sufficient Europe and burden shifting so that America, along with its Pacific allies such as Japan and Australia, can focus on balancing the rise of China. The first will not happen. An occasional lone German frigate in the Indo-Pacific as a solidarity gesture notwithstanding, it is foolish to divide resources in such a way. Western Europeans have different interests from the East and will continue to take advantage of American engagement in Europe, to free-ride, with occasional rhetorical solidarity. A much more prudent strategy is to force a Europe defended by Europeans with only American naval and as a logistics provider of last resort with the US re-oriented towards Asia. West Europe will not be serious about the continent’s defense as long as Uncle Sam is there to break the glass during a fire.

Despite repeated warnings and frustrations, decisions to the contrary are political, not material or structural. A “dormant NATO” strategy that allows the US to shift the security burden to Europe rapidly must be one of the highest priorities.

End Notes

1 “China’s Swelling Nuclear Stockpile Makes It a Growing Rival to U.S., Pentagon Finds,” Wall Street Journal, 29 November 2022; “Strategic Scarcity: Allocating Arms and Attention in Washington”, The National Interest, 5 November, 2022.

2 “Europe accuses US of profiting from war”, Politico, 24 November 2022

3 Data from Ukraine Support Tracker – IFW-Kiel available at

https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/; Also, “US Sending ‘Billions’ to Fund Ukraine Government Operations”, VOA News, 9 July 2022, and “US Eyes Regular Aid Payments to Ukraine, Pushes EU to Do More”, Bloomberg, 2 October 2022

4 For a detailed exploration of failure of Russian invasion, read “Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”, The Royal United Services Institute, 30 November, 2022, available at

https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/preliminary-lessons-conventional-warfightin g-russias-invasion-ukraine-february-july-2022

5‘NATO Expansion: What Gorbachev Heard’, S Savranskaya, & T Blanton, December, 2017, available at National Security Archive at George Washington University (http://nsarchive.gwu.edu) : https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2017-12-12/nato-expansion-what-gorbachev-heard-we stern-leaders-early; Also, RD Asmus, RL Kugler, FS Larrabee, (1993) ‘Building a new NATO’, Foreign Affairs, 72/4. pg. 28–40.

6 MR Gordon, (1994) ‘U.S. opposes move to rapidly expand NATO membership’, (2 January, 1994) New York Times.

7 ME Sarotte (2019) ‘How to Enlarge NATO: The Debate inside the Clinton Administration, 1993–95’ International Security, 44/1, pg. 7–41; and D Brinkley, (1997) ‘Democratic expansion: the Clinton doctrine’, Foreign Policy, 106: 110–27

8 JM Goldgeier, (1999) Not Whether But When: The U.S. Decision to Enlarge NATO Washington, DC: Brookings.

9 For more on opposition to NATO enlargement within United States, see, ME Brown, (1995) ‘The flawed logic of NATO expansion’, Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, 37/1, pg. 34-52; D Reiter, (2001) ‘Why NATO Enlargement Does Not Spread Democracy’, International Security, 25/4: 41-67; KN Waltz, (2000) ‘NATO expansion: A realist’s view’, Contemporary Security Policy, 21/2, pg. 23-38; JJ Mearsheimer, (1994/1995) ‘The False Promise of International Institutions,’ International Security, 19/3, pg. 5-49; 3 May letter to Talbott published in Richard T. Davies, ‘Should NATO grow? A dissent’, New York Review of Books (21 September 1995); MR Gordon, (1994) ‘U.S. opposes move to rapidly expand NATO membership’, (2 January, 1994) New York Times.

10 Strategic Concept, NATO, 2022. Available at https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf

11 See, S Maitra, “Policy Brief: Seeking Equilibrium in East Europe: Burden Shifting in the Baltics”, September 2022, CRA, available at

https://americarenewing.com/issues/policy-brief-seeking-equilibrium-in-east-europe-burden-shifting-in-the-balti cs/

12 “NATO holds first dedicated talks on China threat to Taiwan”, Financial Times, 29 November 2022

13 Graph on Europe and Russia Aggregate Power courtesy of Defense Priorities. Graphs on spending in Ukraine, courtesy of IFW-Kiel, Ukraine War Tracker.

14 S Maitra, “Policy Brief: Seeking Equilibrium in East Europe: Burden Shifting in the Baltics”, September 2022, CRA, available at https://americarenewing.com/issues/policy-brief-seeking-equilibrium-in-east-europe-burden-shifting-in-the-balti cs/; and, S Maitra, “NATO Expansion for Finland and Sweden: A Dangerous and Unnecessary Distraction from U.S. Interests”, May 2022, available at