NATO Expansion for Finland and Sweden: A Dangerous and Unnecessary Distraction from US Interests

Executive Summary:

- Finland and Sweden are following their own interests in Europe. The United States (US) must follow her own interests and reject their addition to NATO.

- A realistic threat assessment would recognize Russia’s depleted force structure and demonstrable inability to threaten Europe as a hegemon in any meaningful way in the foreseeable future. Europe, on the other hand, can balance Russia on its own, if it so wishes, as evident from recent trends.

- US policy should encourage Europeans to shoulder the majority of the security burden in Europe and look to address emerging strategic rivalries elsewhere, especially in the Indo-Pacific.

- At a time of inflation and economic downturn, domestic turmoil, a southern border crisis, and the rise of an adversarial China, additional security commitments in a theatre of low strategic priority, is imprudent and irresponsible.

Introduction:

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the geopolitical considerations of several European nations are changing. Finland and Sweden are now accelerating a transition away from their historic neutrality by attempting to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). NATO is the historic alliance of thirty nations that served as a bulwark against the Soviet Union until the latter’s demise, and its founding treaty includes Article 5, which commits each alliance member to the defense of any other member that is attacked. As a result, the decision on whether to expand NATO to Finland and Sweden must take into account a fundamental consideration: is it in America’s interest to bind itself into a commitment to go to war with a nuclear power over the structural integrity of these two nations? Should the American people be willing to send their servicemen and women for such a national security interest?

“NATO membership would strengthen Finland’s security. As a member of NATO, Finland would strengthen the entire defence alliance,” Finland’s President Sauli Niinisto and Prime Minister Sanna Marin said in a joint statement citing the Russian threat of invasion. “Finland must apply for NATO membership without delay.”

Threat is a combination of intention, power, proximity and capability. For that reason, the lackluster performance of Russia in Ukraine, and corresponding heightened threat perception in Europe, is baffling to realists. After all, what is the hegemonic threat potential of a great power across a continent that cannot provide air cover to its massacred battalions over a pontoon bridge, much less total air supremacy over a theatre of war? It is a pertinent line of inquiry. Wounded by her own folly, Russia remains without any demonstrable hegemonic capabilities to conquer Ukraine and molest parts of Eastern Europe or the wider continent.

This policy brief addresses some fundamental questions arising out of Finland and Sweden’s applications to join NATO. The brief explains the historic neutrality of both Finland and Sweden, as well as their force posture and threat perceptions, and highlights why the West should avoid forcing a scenario that leads to a weakened, cornered and potentially destabilized Russia. The brief then discusses the pro-accession arguments, while addressing why NATO expansion should be rejected. It then addresses the changing security dynamic in Europe, while recalibrating what US policymakers should view as their permanent interests in Europe.

Background:

Finland and Sweden, alongside Austria and Switzerland, were nominally neutral in recent history, a policy that served the countries remarkably well, although the reasons for such neutrality were very different for each. After the Cold War, both Sweden and Finland increasingly shifted towards western security architecture, although that was achieved more often within the framework of the European Union or bilateral ties, especially with the US, than under an explicit NATO umbrella. Finnish neutrality, geopolitically necessary after the Finnish-Soviet war, started to gradually erode with the collapse of the USSR. For example, Finland bought US jets in 1992, and within a few years, joined the EU alongside Sweden and Austria.

While Finnish neutrality was due to geopolitical necessity, up until now, Swedish neutrality was a historic identity. Swedish history was one of true equidistance from both the Western bloc and the Soviet bloc, upholding a uniquely Scandinavian social-democratic position which critiqued both capitalism and communism. Sweden’s last major great power conflict with Russia was centuries back when Sweden was an imperial power. Finland on the other hand, faced Russian aggression as recently as the 1940s. After joining the EU, Finland also participated in NATO’s partnership for peace program, served on NATO missions, and shared intelligence on cyber defense. In 2014 and 2016, both Sweden and Finland were given special preference compared to other non-NATO partners, especially in discussions about interoperability, hybrid warfare and intelligence sharing — domains where Sweden and Finland have major experience regarding Russian threats of hybrid warfare, espionage, military probing by jets and warships, psychological warfare and cyber attacks. Other recent areas of cooperation included disaster relief, maritime security, intelligence gathering, and Arctic security, all of which increased after the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine scrambled the security perceptions in the region. As late as February 2022, Finnish public opinion about joining NATO was stagnant; while in Sweden the public opinion about joining NATO is still more or less evenly balanced. However, the desire to join NATO has gathered remarkable momentum among the ruling elite of both countries as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shattered the status quo.

Prior post-Soviet conflicts involving Russia had some semblance of a casus belli. The Georgians, for example, fired the first shot in 2008, albeit after Russian provocation; the Syrian regime invited Russian air intervention; and the Crimean annexation was a relatively bloodless operation wherein the majority of the pro-Russian population acquiesced to Russian rule without any resistance. However, the Russian invasion of Ukraine was purely a territorial “war of conquest” couched in a regime-change rhetoric, a markedly different event that harkened back to an era before World War II, which changed the European order, and one might argue, propelled Finland and Sweden to rethink their position in the European balance.

Within ten weeks, Finland’s eight decades-long equidistance, and Sweden’s two centuries long neutrality were jettisoned, in favor of unprecedented levels of military bloc formations and foreign military power support pledges, most notably from fellow Scandinavian nations: Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and a post-Brexit Britain.

The existing force postures of Finland and Sweden are uniquely designed to deter Russia unilaterally. The Finnish force of 280,000 is augmented by around 900,000 reservists who are trained for wartime.

Sweden saw major cuts in defense spending and manpower in the immediate post-Cold War era similar to other major powers, but brought back conscription in 2017, after some deliberation following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014.

The Case Against NATO Expansion:

In a recent open survey of Euro-Atlantic foreign policy experts, a question was posed about whether Finnish and Swedish memberships are useful for NATO. The answers ranged from “no doubt,” to “certainly,” and “definitely,” to “straight yes” and “enormously so,” before reaching the broad consensus that the accession of Finland and Sweden would “strengthen the alliance’s defenses and greatly increase security in the Baltic region.” There was not a single voice of dissent.

Support for Finnish and Swedish membership can be categorized into three broad arguments.

The first line of argument – that the Russian threat has morphed to now require NATO protection – is predicated on Sweden and Finland’s threat perceptions. While Russia’s revanchism in Ukraine is clear, the fundamental security dynamic has not changed. At the time of this brief, Russia is suffering from enormous and potentially unbridgeable battlefield setbacks. The Russian dash to Kiev failed, and Moscow is seemingly unable to compensate battlefield attrition, including an overwhelming number of officer class attrition, unthinkable for any other top-tier military and unseen in any other recent conflicts. The Russian battlegroups are not in full operational strength. Russia is unable to fill the gaps created by casualties, troop morale is low, and around a fifth of Russian invasion force hardware have been destroyed. In short, Russia is in no position to continue a “war of conquest,” much less a war of occupation or attrition, without declaring a “total war” that requires vast levels of domestic conscription, which is of course, politically unpopular and potentially volatile for Vladimir Putin. While there have been some indications of a willingness to broaden the Russian military base, it is certainly not in the interests of Western policymakers to incentivize such a development. The much-vaunted Russian military reforms quite clearly did not materialize. The Russian-backed air war over Syria was dependent on Syrian regime troops as cannon fodder, and is materially different and far less costly than a multi-spectrum state-vs-state war of conquest in Ukraine. Russia isn’t capable of the latter.

Despite her historic aspirations, Russia enormously overestimated her own power in Ukraine. Instead, the Russian experience in Ukraine, while a humanitarian catastrophe, has demonstrated long term hardware, personnel, intelligence and training deficiencies, as well as structural issues including endemic corruption, old school planning, authoritarian decision-making echochamber, and low troop morale.

The only development that might reverse an emerging natural equilibrium, is a Ukrainian counterattack on Crimea or somewhere deep inside Russian territory, or a major expansion of an alliance which justifies Russia’s historic and entrenched paranoia, such as a renewed push for further NATO enlargement. A Ukrainian counterattack might result in Russia pulling the nuclear card. It might also solicit a “rally around the flag” effect for this otherwise unpopular and deteriorating war. Barring those, Russian aspiration to be a major revanchist great power in the European balance is practically over, and Russia’s current near total international isolation in 2022 is comparable to her isolation in 1856 or 1921. Meanwhile Ukraine has managed with conscription and compulsory male draft to gather an overwhelming number of men willing to defend their country, and is well supplied with practically unlimited foreign resources and weaponry, an example to other states in the region.

In that light, the idea that Finland and Sweden, with significant military capabilities of their own, need to be in an alliance for protection against Russian revanchism at a time when Russia’s status as a revanchist great power is itself in question, is fallacious, especially with Russia facing a quagmire in Ukraine. The possibility of a Russian invasion and conquest of Finland or Sweden is nearly non-existent.

Likewise, it is also paradoxical to argue that Finland and Sweden need protection, while simultaneously contending that they are uniquely powerful militaries with deterrence capabilities needed for strengthening NATO’s northern frontier.

For any other military or intelligence needs, bilateral or EU frameworks are more than sufficient.

The Need for American Restraint:

America’s strategic interest in the European balance is not under any significant threat from a potential hegemonic challenge that seeks to dominate the entirety of European landmass under one army and one flag.

The difference in this instance was that the British aspired to attain this objective through a delicate “balance of power” within the continent with minimal interference to tilt the balance as and when required, while cautiously avoiding continuous engagement in the domestic affairs of European countries, or commitments about spreading rights and values. While the American interest in ensuring no hegemonic threat in the European continent remained intact, the American grand-strategy, especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, deviated from an earlier realist one. It in turn sought to institutionalise peace across the continent, while ensuring fundamental human rights in every corner – or in the words of John Mearsheimer and Barry Posen, ensure primacy and spread “liberal hegemony.”

Unfortunately, that resulted in the atrophy of Europe’s traditional security providers–the western powers–and at the same time, encouraged free riding on American treasure and muscle. The institutionalisation of peace, first through an expansion of NATO and then through support of the EU, also resulted in buckpassing wherein Western European great powers are perfectly content to wave the EU flag but simultaneously rely on the US tax-funded security subsidies. The Eastern European powers are permanently activist with lofty rhetoric about values and human rights, meanwhile leaving the security burden in large part to be covered by the US. Both Western European states and the Eastern European states act rationally based on their narrow security interests, and that is perfectly understandable. The narrow American interest is the only one ignored in this context.

Several American presidents and policymakers, from Dwight Eisenhower to John Kennedy to Donald Trump, have attempted to grapple with European free-riding and “buckpassing.”

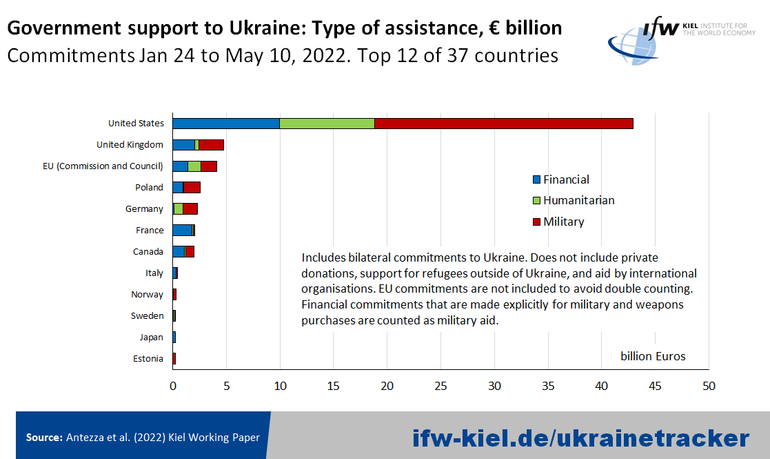

Further enlargement of NATO in the current scenario risks doubling down on American security commitments. That, coupled with unlimited financial aid for Ukraine, or further permanent troop additions in theatres of Eastern Europe, reverses all the recent gains that were made to require Europe to fund more of its own security requirements. In the face of renewed Russian aggression, a one-time US infusion of resources and weaponry to Ukraine may have been understandable, as were enhanced bilateral alignments with Finland and Sweden. However, those efforts should have been accompanied by corresponding requirements that rich European states shoulder the long-term localized security architecture and endure the majority of the future cost. This is especially so given that a localized war in the periphery of their continent is of far more strategic significance to Europeans, than it is to the United States. As the accompanying chart demonstrates, it is not justifiable to American taxpayers that Europe is once again subsidized by the US.

Instead, the Biden administration is absolutely determined to double down on the failures of the post-Cold-war strategy in supporting the addition of Finland and Sweden to NATO. The shift of NATO frontiers further to the east and north, and adding more buffer states, would only disincentivize rich Western European nations from providing security in their own backyard. With the rising threat of a near-peer rival in China, severe economic downturn, and looming strategic trade-offs, committing more to NATO is irresponsible and imprudent.

Conclusion:

A fast-track process for Finland and Sweden’s NATO membership is now underway, at the behest of those European states who are taking advantage of the situation and war hysteria to further enlarge an already bloated and diluted alliance. Consolidating an arrangement that has worked well for them in the past few decades is an understandable desire, but it does not correspond that it has worked well for the US. Policymakers in the United States should ignore the popular currents and encourage open public debates about the limits of NATO’s constantly mutating frontiers and fluid commitments.

Finland and Sweden are in no real danger of any invasion, and neutrality worked well for them. Russia is a shadow of its former self, with a broken military and damaged economy due to an attritional war of choice, and collectively, Europe massively outspends Russia. In fact, Germany, France, and Britain combined are more than capable of providing deterrent forces in the Baltics, and have their own nuclear umbrella. Neither Finland nor Sweden adds enough to the security of the alliance to justify the additional costs. Adding them would mean two more states as protectorates for whom the US would be treaty bound to go to a nuclear war.

Neither war hysteria, nor a desire to punish Russia, nor sympathy for democratic values and human rights should affect narrow strategic calculations in such a permanent way. Instead, the Russian debacle in Ukraine demonstrates that it is increasingly time for the US to reorient away from Europe and focus on more pressing issues such as the southern border, inflation, and the rise of China.

Americans are already familiar with George Washington’s warnings about avoiding “passionate attachments” and interweaving destinies with any parts of Europe. The emerging global order encourages everyone to pay heed to another George. In 1822, after the collapse of Napoleonic France and resulting multipolarity in which Great Britain enjoyed overwhelming preponderance and faced no long-term hegemonic threat from Europe, the British conservative foreign minister George Canning coined the guiding principles of “non-intervention and every nation for itself…in a balance of power; respect for facts, not for abstract theories; respect for treaty rights, but caution in extending them.” Those principles underscored a certain conservative realism that served Britain well for over a century. While unfashionable in the post-modern world, now is the time for America to look back to the wisdom of an era functionally similar to ours.