Fiscal Update: Appropriations Process at Congress’ Summer Break

As the Congress enjoys its 6-week Summer break, it’s a good time to review its progress on annual spending measures. These bills are written by the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate to provide spending authority for the salaries of the military, federal workers, and many of the programs Federal workers administer. Failure to complete this legislative task by the September 30 end of the fiscal year results in a partial government shutdown.

Under regular order, the aggregate maximum spending for the 12 appropriations bills is established by a budget resolution that has been agreed to by both the House and the Senate. (The budget resolution is not signed by the President.) The agreement on maximum spending levels provides discipline and unanimity of purpose as the House and Senate prepare spending legislation for floor consideration and, ultimately, presentation to the President for signature.

The House and Senate have not agreed on a budget resolution for fiscal year (FY) 2025. There was an agreement last year on discretionary spending limits for FYs 2024 and 2025, established in the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA; PL 118-5). In the absence of a new budget resolution, the FRA discretionary limits should guide preparation of the annual spending bills.

Unfortunately, the FRA was a sham from the start. Then-Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy cut a side-deal with Democrats to allow $71 billion in emergency-designated spending enacted prior to the FRA to continue in the future—but did not share that detail with his Republican colleagues. As awareness of the side deal increased, House Republicans moved away from it.

As a result, the appropriations process has proceeded on different tracks in the House and Senate, and a continuing resolution (CR) will be needed to prevent a government shutdown. The spending cabal wants to complete negotiations on full-year spending bills when the current Congress comes back for a lame-duck session after the election. It is certain those negotiations would blow through the FRA spending caps conservatives thought were too high to begin with, and completely cut the next President out of the deal. Conservatives must insist that the CR last until after the inauguration of the next President to preserve the ability of the newly elected President and Congress to make spending decisions as is traditionally the case. They should also support the call of the House Freedom Caucus to safeguard election integrity as part of the CR. Further, conservatives must keep the negotiations on the discretionary spending limits separate from those on extending the temporary increase in the debt limit, which will expire early in 2025, to preserve their leverage to use their votes on the next debt limit increase to obtain lasting spending restraint.

How did we get here?

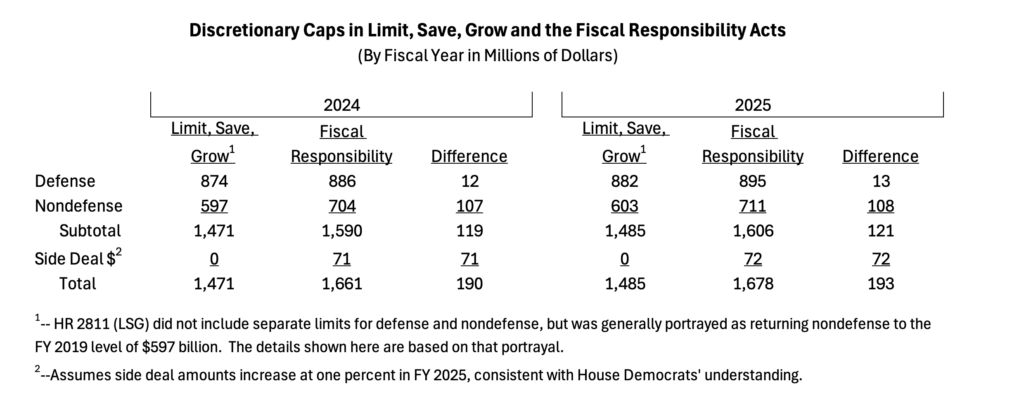

Early in the 118th Congress, conservatives in the House coalesced around the Limit, Save, Grow Act (LSG; HR 2811) in exchange for a vote to increase the debt limit. The LSG provided for a debt limit increase of $1.5 trillion or a suspension of the debt limit through March 31, 2024, whichever came first, and discretionary caps that would roll back the massive increases in nondefense discretionary spending to FY 2019, that is, pre-Covid-19 pandemic levels.

The LSG passed the House with only Republican votes in late April 2023 but was not considered in the Senate. Instead, the majority leadership began bipartisan negotiations on a compromise, which became the FRA.

As can be seen from the table below, spending in the FRA is $240 billion higher than in LSG over the two years of the agreement, with $215 billion of that amount in nondefense spending. While the FRA holds to the one percent increase in annual spending supported by the House with LSG, it does so at a nondefense level that is almost 20 percent higher than the pre-Covid level. When the McCarthy side-deal is included, spending would be $383 billion (13 percent) higher than the wishes of the Republican caucus.

When the FRA was being negotiated, the government was operating under a continuing resolution for FY 2024 (that is, at the levels enacted for FY 2023), supplemented by $71 billion in emergency-designated appropriations. The $71 billion was not really for any emergency but instead was largely for clean energy scams and other routine spending provided by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (PL 117-58) and the Safer Communities Act (PL 117-159).

Democrats, who were in the majority in the House when the $71 billion was signed into law, understood that the agreement for a one percent increase in FY 2025 included the $71 billion in the FY 2024 base. Republicans, who did not support the $71 billion when in the minority, understood that the $71 billion was one-time spending that should be excluded from the computation. The “compromise” was the $71 billion being agreed to outside the statutory caps paid for with rescissions to money never intended to be spent, a common gimmick. With the removal of McCarthy from the office of Speaker, this arrangement is now in jeopardy.

The spending cabal in Congress wants to exploit these differing understandings to force a renegotiation of top line FY 2025 levels after the November election. They say it will be good to clear the decks for the next President, but the cabal also expects that the renegotiation will result in significantly higher spending caps than conservatives reluctantly agreed to in the FRA.

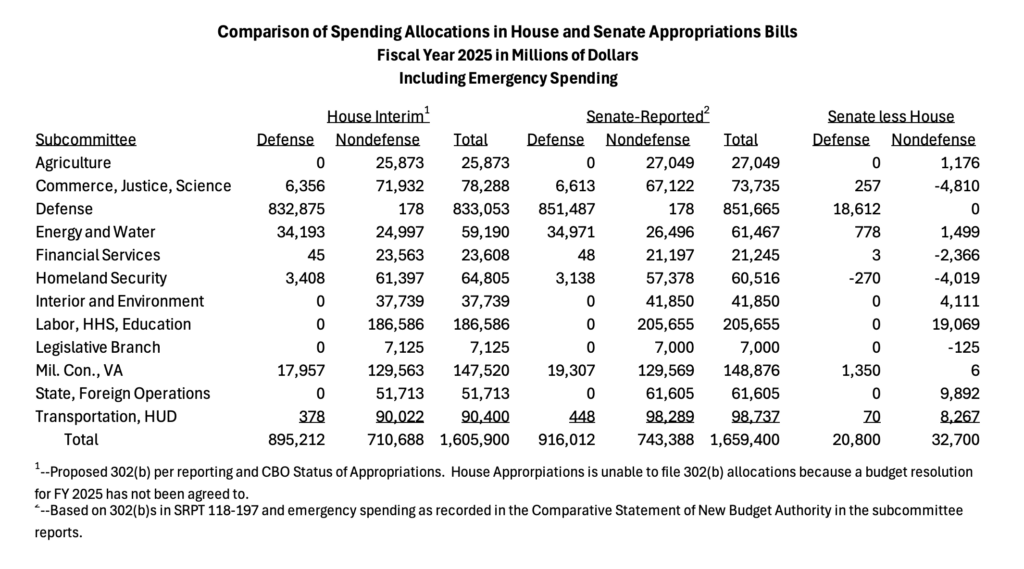

Spending Levels in the House and Senate Appropriations Bills

Each of the 12 subcommittees of the Appropriations Committee is given a spending allocation, known as a 302(b), to provide for the needs of the agencies and programs under its jurisdiction. Both the House and Senate have set their 302(b)s at the level of the caps set in the FRA, but Senate appropriators on a bipartisan basis have added almost $54 billion in emergency spending not subject to the cap to bring their bills closer to the amounts Democrats have argued they are owed from the FRA plus $71 billion McCarthy side deal.

The table on the next page shows the spending allocations by subcommittee for House and Senate. As can be seen from the table, despite having $54 billion in higher spending overall, the Senate still provides substantially fewer resources than the House for several subcommittees (Commerce, Justice, Science; Financial Services; and Homeland Security). The Senate also provides substantially higher spending than the House for the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education subcommittee ($19 billion, including higher funding for illegal immigrants, labor law enforcement, and a $100 increase to $6,435 in the maximum Pell grant), the State and Foreign Operations subcommittee ($10 billion, including higher spending for State Department operations, bilateral assistance, and contributions to international organizations), and the Transportation and Housing and Urban Development subcommittee ($8 billion, largely from declaring routine housing voucher renewals to be an emergency requirement).

In the case of the Homeland Security bill, the House’s higher spending provides $4.1 billion for illegal alien custody and removal (up $670 million from the prior year) and $600 million for border wall, as well as maintaining a force of 22,000 Border Patrol Agents without resorting to emergency appropriations. This difference alone suggests that the Senate will want to increase the $54 billion in emergency-designated spending in negotiations with the House if priorities like border security are to be appropriately funded.

While the higher costs of securing the border could be offset by reducing some of the higher spending in Senate-Reported bills like the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education (Labor-HHS) appropriation bill, it is not at all clear that Republican Senators on the Appropriations Committee will readily agree to savings from the committee-reported levels.

The Senate Appropriations Committee reported 11 of 12 bills prior to the recess, leaving only the Homeland Security bill for final Committee action. Of those 11, five were reported without any opposition. (There are 14 Republican Senators on the 29-member committee.) The largest number of votes against the remaining six bills was the five no votes received by the State-Foreign Operations bill. The Senate-Reported Labor-HHS bill, which has the largest dollar increase over its House-Reported companion, received only three no votes.

In contrast, the House Appropriations Committee was able to report all 12 of its bills to the floor at the level of the FRA caps. Five of those bills were passed on the House floor prior to the recess (Defense, Homeland Security, Interior-Environment, Military Construction-Veterans Affairs, and State-Foreign Operations). Debate on the Energy-Water bill has concluded, but a vote has not yet been called. The Legislative Branch bill did not pass the House, in part because of a proposed 3.5 percent increase in spending above enacted levels.

Because the Senate did not bring bills to the floor prior to the recess, it is unclear whether Republican Senators who are not on the Appropriations Committee are ready to support the higher levels of spending endorsed by their colleagues who serve on Appropriations.

Conclusion

The appropriations process to date makes clear that conservatives are being set up for a renegotiation of the FRA’s two-year budget deal. While previous multi-year cap deals have held for about three years, and two-year cap deals held during the Trump administration, in the current environment, the spending cabal cannot even honor a two-year deal. Instead, the uniparty wants to move to one-year deals that would make both the congressional budget resolution and the debt limit obsolete.

In the uniparty’s ideal scenario, leadership would negotiate a bill both to set the annual spending caps and to suspend the debt limit, providing a path for appropriations to proceed at the cap level. That scenario would (1) eliminate uncomfortable debate on a budget resolution and (2) limit the power of individual legislators (and bind a future president’s ability to tame inflation for multiple years) to leverage their votes on the budget resolution and debt limit legislation to force changes in spending priorities.

If leadership succeeds in combining annual spending caps and the debt limit in a single bill for the second year in a row, they can argue the precedent is the new normal. Leadership would usurp even more authority from individual legislators, diminishing our republican form of government.

Conservatives won a one-percent growth in FY 2025 spending in the FRA and should not give that up—particularly since the House has been able to pass bills at the levels of the FRA caps. In fact, conservatives should push forward to obtain other parts of their agenda, like the SAVE Act to keep illegals from voting, as advocated by the House Freedom Caucus.

It is critical that conservatives insist that the CR last until after the inauguration of the next President so that they may maintain leverage over the final spending levels, and that the CR be passed with Republican votes. Elections have consequences, and the new Congress and President should complete the work that this Congress and President have avoided all this year. Further, conservatives must keep negotiations on FY 2025 spending levels separate from the negotiations on the next increase or suspension of the debt limit. Allowing the negotiations to be combined will diminish conservatives’ leverage for this negotiation (vote for higher spending or be blamed for default) and may set a lasting precedent that diminishes their leverage on fiscal legislation in the future.