Primer: The Shameful Scandal of Biden’s Missing Illegal Alien Children

Synopsis

Children apprehended at the southern border without a parent in the United States to care for them, also known as unaccompanied alien children (UACs), are vulnerable to trafficking, exploitation, and forced labor. The Biden administration facilitated these vulnerabilities through its open borders policies, failure to enforce the law, repeal of existing regulations and agreements, and fast-tracked placement of children into homes with incomplete vetting. The result was the disappearance of more than three hundred thousand of these children, whose safety, freedom, and well-being were put at risk. The Trump administration has rapidly moved to find these children and ensure their safety, pushing through record amounts of funding for border security, mobilizing federal law enforcement for wellness visits, and strengthening background checks. To bolster these efforts, the administration could pursue expanded information-sharing agreements, particularly between the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and continue to perform safety and well-being checks. Congress should address the root cause of the problem by reforming the law to enable law enforcement to quickly return UACs to their home countries.

Background

A UAC is defined under federal law as an individual under the age of eighteen with no lawful U.S. immigration status and no parent or guardian present or able to care for him or her in the United States.1 Members of this group are at particular risk of being subjected to sexual violence, prostitution, forced labor, forced domestic help, and other forms of exploitation and abandonment. Creating the opportunity for even one child to be abused is not acceptable, and the sad reality is that these harms are pervasive.

The majority of UACs apprehended at the border are held in custody for only seventy-two hours. UACs from contiguous countries (Mexico and Canada) can be rapidly returned to their home country if they have not been trafficked, a possibility that effectively dissuades entry. Section 235 of the 2008 Trafficking Victims Prevention and Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) requires that UACs from noncontiguous countries be released into the custody of the HHS Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).2 Once the child is there, ORR cares for him or her and finds and vets a sponsor to take custody of the child. First-priority sponsors are the parents of the UAC, but distant relatives or even nonrelatives can be selected. After a sponsor is approved, ORR releases the UAC into his or her custody and is no longer responsible for the child. In the following thirty days, ORR attempts to reach the sponsor for a safety and well-being check, but sponsors have no obligation to respond. The transfer of physical custody does not grant legal custody to sponsors who do not already have it, and this loophole leaves many children in legal limbo. Making matters worse, during the Biden administration, ORR was often opaque when dealing with state and local law enforcement, refusing to share details about UACs and sponsors and reducing the office’s ability to investigate abuse.3

According to internal policy, once UACs are out of ORR’s custody, or after one hundred days, United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents can serve them with a Notice to Appear (NTA) in immigration court. Serving the NTA and requiring subsequent court appearances are the main methods the law provides the federal government to verify that these children are safe.4 UACs who fail to appear in court are at higher risk of trafficking, exploitation, and forced labor. ICE’s awareness of UACs’ locations is also valuable because of the potential risk some UACs pose to communities. A minority are violent criminals, and both UACs and those over age eighteen posing as minors have committed heinous offenses.5

An August 2024 report from the DHS Office of the Inspector General found that from 2019 to 2023, nearly half a million UACs were referred to ORR. Of those, 32,000 UACs failed to make their court dates, and 291,000 were not served an NTA at all.6 In sum, approximately 325,000 UACs fell off the government’s radar during this time period, as ICE attorneys, already stressed by the massive influx of illegal aliens at the border, were encouraged to exercise prosecutorial discretion by not filing NTAs and dismissing cases for UACs.7 In other words, the Biden administration made enforcing the law as it related to children a nonpriority. These children, deprived of the chance for their safety to be verified, were left to their sponsors and the mercy of a gutted ORR vetting process.

The Biden administration, in removing sponsor screening guardrails at every turn, willfully chose to endanger the lives of innocent children for political optics. For starters, background check requirements for sponsors were slashed. In 2021, field guidance changed vetting requirements for most parents, removing proof of address requirements, fingerprinting, and background and identification checks for other adults in their household.8 Another guidance document eliminated household background check requirements for most nonparent family members.9 Further reducing ORR’s capacity to vet sponsors, the Biden administration also replaced a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between ORR and DHS. The first Trump administration’s MOA had allowed DHS and ORR to mutually assist one another, with ORR supplying information about potential sponsors and members of their households and DHS using the information to provide the criminal and immigration histories of potential sponsors.10 While the previous MOA required ORR to share fingerprints, date of birth, biographical data, identification documents, and biographical information, the Biden administration’s MOA required ORR to share only the sponsor’s name, relationship to the UAC, and address.

Even that information was suspect, and a March 2025 report from the DHS Office of the Inspector General found that more than thirty-one thousand addresses provided to ICE by ORR were either blank, undeliverable, or missing apartment numbers; addresses were often wrong and sometimes did not exist; and ORR failed to update ICE on the results of safety and well-being checks or notify the office when UACs changed address. Additionally, ICE had no way to locate UACs who had run away from ORR, some of whom were violent criminals.11

Significant numbers of UACs were also placed with non-related individuals, a sponsor category with the highest risk of trafficking and engaging in forced labor. The lack of DNA testing and the acceptance of easily forged foreign documents give little confidence that ORR did not provide children to sponsors fraudulently claiming to be their parents. Regardless of the sponsor category, ORR made some attempt to contact the sponsor within thirty days of receiving a placement, calling at least three times.12 Even that weak measure met with limited success, and in the first fifteen months of the Biden administration, an estimated eighty-five thousand UAC sponsors did not pick up the phone.13 For children in those sponsors’ custody, there was no assurance whatsoever that they were safe. Even when ORR was able to make contact, a phone call provided no verification that the child placed in a sponsor’s care was safe. Compounding the failure, even when ORR did receive notifications of concern and reports of human trafficking, tens of thousands of those reports were ignored or dismissed.14 By contrast, the second Trump administration’s processing of the data has already resulted in hundreds of leads and dozens of arrests and arrest warrants.15

The final way the Biden administration has failed these children is by ending rapid DNA testing of suspicious families at the southern border. If the administration had not done so, the number of apprehended UACs would likely have been higher.16 Under the program initiated by the first Trump administration, 8.5 percent of children tested were unrelated to those with whom they were traveling.17 The Biden administration allowed the DNA testing program to lapse, making it easier to smuggle children and adults across the border in fraudulent family units. Also not included in the UAC numbers are “gotaways” detected by the Border Patrol but not apprehended. While demographic information on such aliens is unknown, it’s fair to assume some of the more than 1.7 million “gotaways” were unaccompanied children.18

What’s Being Done?

The Trump administration’s efforts to tackle the problem have been significant. Both DHS and HHS are actively working to find and rescue these missing children.

Starting on day one, President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 14159, implicitly rescinding the memorandum from former DHS secretary Alejandro Mayorkas that mitigated the NTA process. That order paved the way for the DHS to act, and soon after, it issued a memorandum coordinating ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) and Enforcement and Removal Operations, with support from the DHS Center for Human Trafficking, to locate, contact, and serve immigration documents to missing UACs.19 Key priorities include locating UACs who failed to attend an immigration hearing, UACs whom ORR was unable to contact, UACs who had run away from ORR, and UACs who were released to unrelated sponsors. These constitute risk categories for sex trafficking and forced labor. Secondary priorities include finding UACs with gang, terrorist, or criminal backgrounds and UACs with executable orders of removal.

DHS and ORR also enlisted federal law enforcement agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to perform welfare checks on UACs.20 The checks consist of interviews of UACs and their sponsors, as well as checks of their living conditions. ICE is then notified of any children who are in danger. By the beginning of May, more than one hundred children had been removed from their sponsors and returned to federal custody, a grim indictment of the sponsor policy.21Other initiatives are also underway. ORR now requires fingerprinting, DNA testing, and income verification for sponsors to verify their identity and familial status. The backlog of sixty-five thousand reports of concern about UACs is 28 percent cleared.22 HHS and DHS are drafting a new Memorandum of Understanding and implementing recommendations from the August 2024 and March 2025 reports by the inspector general. This effort aims to increase cooperation between HHS and ICE, prioritize serving the NTA backlog, and establish systems to document when UACs fail to appear for immigration hearings. These efforts have been invaluable in fixing the errors of the previous administration.

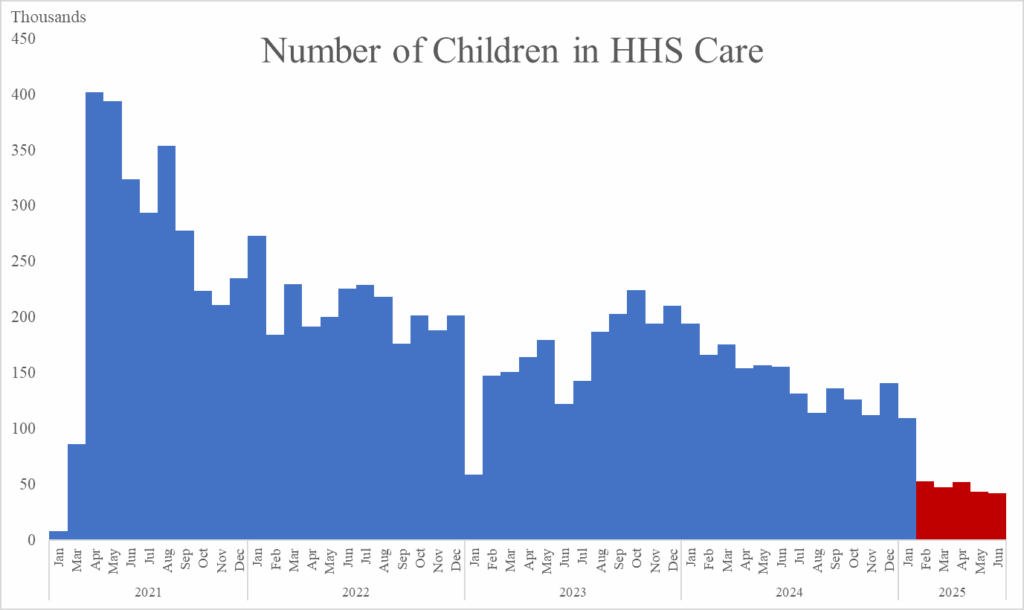

Broader border control policies have also dramatically reduced encounters with UACs, and since February, the number of children in HHS custody has been lower than at any point in the Biden administration.23 The recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) provided more funding for border enforcement. These resources are necessary to ensure sufficient staffing to process outstanding NTAs and UACs. This one-two punch will not only find more missing children but also deter parents from sending their children on a harrowing journey to the United States.

What More Can Be Done?

The current focus on locating missing children by HSI, ICE generally, and other federal law enforcement should continue apace now that the OBBBA has become law. Under President Trump’s leadership, HSI is once again prioritizing the protection of vulnerable children and enforcing the rule of law across borders. With its extensive domestic and international footprint, including 235 offices across the United States and a global presence in more than fifty countries, the agency has the reach and capability to meet these threats head-on. HSI is well positioned to locate the tens of thousands of children lost under the Biden administration’s reckless open-border policies. Continued focus on and escalation of these initiatives are essential to dismantling trafficking networks, restoring accountability, and safeguarding children who have been exploited. HSI must continue to expand its efforts—finding every missing child, dismantling every complicit network, and restoring order and accountability to an immigration system that was deliberately broken.

As a complementary effort, HHS and DHS should consider re-implementing broad information sharing about UACs and their sponsors between ICE and ORR. Similar information-sharing agreements might also be made with other federal agencies. One possible collaborator is the Department of Labor, which could coordinate with ICE to find and prevent forced labor, bearing in mind that two-thirds of UACs are working illegally in full-time jobs, often in unsafe conditions.24

Ultimately, a broader paradigm shift may be necessary. The present system functions as a delivery service for traffickers. In the best of circumstances, it brings children to negligent parents who abandoned them to the long and dangerous journey north, and at worst, it abandons them to lives of sex slavery and forced labor. As the Center for Renewing America argued in a 2021 paper, the Immigration and Naturalization Act should be amended to create a specific process to safely and efficiently return UACs to their country of origin.25 In cases where there are concerns about a child’s welfare in his or her home country, transfer to that nation’s Child Protective Services or its equivalent would ensure safety while eliminating the perverse incentives of the current system. This strategy would also remove the need for placements with sponsors, who, in many cases, should be deported themselves and/or prosecuted for neglect. A smaller step with similar consequences would be eliminating the TVPRA’s distinction between UACs from contiguous and noncontiguous nations, a change supported by both immigration hawks and President Barack Obama in 2014.26

Conclusion

To properly track and account for all existing UACs and to deter new children from illegally entering the United States, border enforcement must be prioritized as a vital part of maintaining American sovereignty. The Biden administration’s non-enforcement of the law, gutting of vetting processes, and evisceration of safeguards were all conscious choices that lost track of hundreds of thousands of children, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation, trafficking, and forced labor. While the Trump administration is working to find these missing children, Congress should ensure that such failures can never occur again.

Endnotes

1. 6 U.S.C. § 279 (2002)

2. William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 § 235, 8 U.S.C. § 1232 (2008)

3. Minority Staff Report (2024, November). The Biden-Harris Administration’s Failure to Protect Unaccompanied Children from Abuse and Exploitation. Minority Staff of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/orr_minority_staff_report.pdf

4. The other agency that might have knowledge of UACs is United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). USCIS has first jurisdiction over Special Immigrant Juvenile classification and handles asylum applications, and ICE can delay serving an NTA until proceedings finish. These cases account for only 0.3 percent of the unserved NTAs.

5. Cuffari, J. (2025, March 25). ICE Cannot Effectively Monitor the Location and Status of All Unaccompanied Alien Children After Federal Custody. U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2025-03/OIG-25-21-Mar25.pdf

6. Cuffari, J. (2024, August 19). Management Alert – ICE Cannot Monitor All Unaccompanied Migrant Children Released from DHS and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Custody. U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2024-08/OIG-24-46-Aug24.pdf

7. Doyle, K. (2022, April 3). Guidance to OPLA Attorneys Regarding the Enforcement of Civil Immigration Laws and the Exercise of Prosecutorial Discretion [Memorandum]. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of the Principal Legal Advisor. https://www.ice.gov/doclib/about/offices/opla/OPLA-immigration-enforcement_guidanceApr2022.pdf

8. Office of Refugee Resettlement (2021, March 22). ORR Field Guidance #10, Expedited Release for Eligible Category 1 Cases. Administration for Children and Families. https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/orr/FG-10%20Expedited%20Release%20for%20Eligible%20Category%201%20Cases%202021%2003%2022.pdf

9. Office of Refugee Resettlement (2021, March 31). ORR Field Guidance #11, Temporary Waivers of Background Check Requirements for Category 2 Adult Household Members and Adult Caregivers. Administration for Children and Families. https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/orr/FG-11%20Temporary%20Waiver%20of%20Background%20Check%20Requirements%202021%2003%2031.pdf

10. Memorandum (2018, 13 April). Memorandum of Agreement Among the Office of Refugee Resettlement of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Customs and Border Protection of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Regarding Consultation and Information Sharing in Unaccompanied Alien Children Matters. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement, and U.S. Department of Homeland Security Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. https://www.texasmonthly.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Read-the-Memo-of-Agreement.pdf

11. Cuffari, J. (2025, March 25). ICE Cannot Effectively Monitor the Location and Status of All Unaccompanied Alien Children After Federal Custody. U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2025-03/OIG-25-21-Mar25.pdf

12. While it was policy to make calls to all children and their sponsors within thirty to thirty-seven days, a February 2024 HHS Office of the Inspector General report found that in 22 percent of UAC cases, ORR follow-up calls were not completed in a timely manner. Grimm, C. (2024, February). Gaps in Sponsor Screening and Followup Raise Safety Concerns for Unaccompanied Children. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-07-21-00250.pdf

13. Hearing Wrap Up: ORR Director Fails to Answer Questions About 85,000 Lost Unaccompanied Alien Children, Flawed Vetting of Sponsors, and More (2023, April 18). U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. https://oversight.house.gov/release/hearing-wrap-up-orr-director-fails-to-answer-questions-about-85000-lost-unaccompanied-alien-children-flawed-vetting-of-sponsors-and-more/

14. Grassley Exposes Biden-Harris Backlog of Criminal Complaints in Unaccompanied Migrant Children Program (2025, May 29). Office of Senator Chuck Grassley. https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-exposes-biden-harris-backlog-of-criminal-complaints-in-migrant-children-program

15. Ibid.

16. Solomon, J., & Smith, A. (2023, May 22). Biden to End Familial DNA testing at Border, Key Deterrent to Fraud and Child Trafficking. Just the News. https://justthenews.com/government/security/exclusive-biden-end-familial-dna-testing-border-key-deterrent-fraud-entry

17. Ibid.

18. Border Sector Chiefs Confirm Operational Impacts of Border Chaos: Increased Gotaways, Closed Checkpoints, and Empowered Cartels (2023, December 20). U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security. https://homeland.house.gov/2023/12/20/border-sector-chiefs-confirm-operational-impacts-of-border-chaos-increased-gotaways-closed-checkpoints-and-empowered-cartels/

19. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2025). Unaccompanied Alien Children Joint Initiative Field Implementation [Memorandum]. https://nipnlg.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/2025-ICFO-22246-001.pdf

20. LeVine, M., Sacchetti, M., Roebuck, J., Leonnig, C., & Nakashima, E. (2025, April 10). FBI, Other Criminal Investigators Drafted for Welfare Checks on Migrant Children. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/2025/04/10/trump-migrant-kids-welfare-checks/

21. Seitz, A., & Richer, A. (2025, May 2). Door Knocks and DNA Tests: How the Trump Administration Plans to Keep Tabs on 450,000 Migrant Kids. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/trump-migrant-children-immigration-sponsors-border-7a5004c88260a57ea194631a13e5941e

22. Grassley Exposes Biden-Harris Backlog of Criminal Complaints in Unaccompanied Migrant Children Program (2025, May 29).

23. HHS Unaccompanied Alien Children Program. HealthData.Gov. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://healthdata.gov/National/HHS-Unaccompanied-Alien-Children-Program/ehpz-xc9n/

24. Hearing Wrap Up: ORR Director Fails to Answer Questions About 85,000 Lost Unaccompanied Alien Children, Flawed Vetting of Sponsors, and More (2025, June 11). U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. https://oversight.house.gov/release/hearing-wrap-up-orr-director-fails-to-answer-questions-about-85000-lost-unaccompanied-alien-children-flawed-vetting-of-sponsors-and-more/

25. Center for Renewing America (2021, July 20). Policy Brief: A Comprehensive Overview of the Crisis at the U.S. Southern Border. https://americarenewing.com/issues/policy-brief-a-comprehensive-overview-of-the-crisis-at-the-u-s-southern-border/

26. President Barack Obama (June 30, 2014). Efforts to Address the Humanitarian Situation in the Rio Grande Valley Areas of Our Nation’s Southwest Border. White House Office of the Press Secretary. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/06/30/letter-president-efforts-address-humanitarian-situation-rio-grande-valle