Primer: Deterioration, Abuse, and Waste in the Shipbuilding Industry

Synopsis

American shipyards have declined significantly in both productivity and number. Despite efforts to modernize, the Navy remains unable to acquire warships at the rate a contemporary war would require. It is increasingly the case that mere technological superiority will not suffice to counter infrastructurally capable, near-peer threats either. A fleet marred by delays in production would be incapable of responding to the logistical demands of the current naval theater. Repairing this sector, then, is of the utmost importance for deterring rising maritime powers such as China from over projecting against the United States and its interests. Yet little has been done to counteract this downward trend in American shipbuilding. In contrast to President Donald Trump’s first term, which saw over twenty ships acquired by the Navy, not a single ship was added to the fleet’s total during the Biden administration.

The general trend of stagnation is largely attributable to incompetent and bureaucratic overregulation whose mismanagement was encouraged under Biden. Hundreds of millions in maritime-related funding were directed towards diversity, climate, and other woke initiatives at the expense of efficiency and merit. Pentagon officials, who have demanded billions to recuperate the defense industrial base, have yet to meet a single one of their acquisition goals. The outdated and potentially subversive strategies that military officials use in equipment acquisition must be held to account or reconfigured entirely. For the United States’ status as the world’s dominant sea power to be maintained, radical reform is necessary. The Trump administration has the opportunity to restart the successful policy of his first term and tear down the deep state roadblocks erected by the Biden administration. Through the newly announced shipbuilding office, Trump could direct the Department of Defense to begin expanding the number of shipyards constructing the Navy’s fleet, loosen regulations lobbied for by big shipbuilders, and provide financial rewards for smaller businesses seeking to acquire and revitalize the dozens of abandoned shipyards scattered across America’s coasts.

The State of the Shipbuilding Industry

After World War II, the United States had seventy-two shipbuilding yards manufacturing large1 naval or merchant ships.2 As of today, there are only twenty builders in service. Twelve of these yards are more than fifty years old, and five of them are more than one hundred.3 Only six are actively producing large naval ships and submarines. These shipyards are split in ownership between three contractors, and one is based in Australia. In 1990, by contrast, the Navy had eight U.S.-based companies under contract to manufacture its ships.4 In a 2022 report on its dealings with the private sector, the Department of Defense euphemistically refers to its declining investment in American shipbuilding as “consolidation.”5 The obfuscation attempted by the use of this term becomes apparent once a comparison of the United States’ current shipbuilding rate is made against its historical numbers. For example, from 2011 to 2022, the Virginia-class attack submarine had been acquired at a rate of two boats annually. The completion rate since 2022, however, has been about 1.2 to 1.4 submarines per year.6 The Navy’s goal is to increase Virginia-class submarine production back to two yearly acquisitions as well as an additional Columbia-class submarine, but this effort would require five times the tonnage the industry was contracted to produce prior to 2010.7 According to Naval Operations Admiral Mike Gilday, however, an insufficient and deteriorating industrial capacity has been and continues to be a significant obstacle to this objective.8

Competing with China

While the American shipbuilding industry diminishes in conjunction with its fleet, China’s continually expanding industry has allowed it to exceed the United States’ number of naval platforms by seventy-four,9 and that gap is expected to grow by another hundred ships by 2035.10 Although the gross tonnage of its fleet remains three million less than that of the United States, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy is set to surpass even that by 2040.11 The United States’ shipyards have a cumulative manufacturing capacity of less than 100,000 tons, whereas China’s is about 23.5 million—232 times that of the United States.12

The United States’ share of the global shipbuilding industry has dwindled almost to nonexistence in the past few decades. China represents 56 percent of the worldwide shipbuilding industry, Europe a modest 10.5 percent, and the United States barely a quarter of a percent.13 This is attributable mainly to the extensive investment China has placed into its maritime trade. China’s mass-manufacture of goods—facilitated in part by the outsourcing of American workers and weak trade policy—has necessarily produced demand for a high maritime capacity. With the majority of its corporations being state-owned or having party members on their board, the Chinese government can centrally control its economy and industry, thereby enabling it to appropriate resources from its maritime boom for a vast naval buildup.14 Its official policy of Military-Civil Fusion (MCF) requires industry leaders to incorporate military and state officials’ input into their final product.15 Consistent with that policy, the PLA has retrofitted civilian roll-on/roll-off vessels with stern ramps and communication equipment to better facilitate amphibious assaults.16

Contrast this model to that of the United States, where influence on the country’s industrial base is mostly accomplished through grants and bids to the private sector. Many of these bids aren’t even natively acquired. Nearly a quarter of the Sealift Command’s roll-on/roll-off arsenal was produced by foreign companies.17 The Maritime Administration (MARAD) in its entirety operates just forty-two roll-on/roll-off ships—the same amount that the Chinese State Shipbuilding Company alone will produce at just one of its shipyards in under three years.

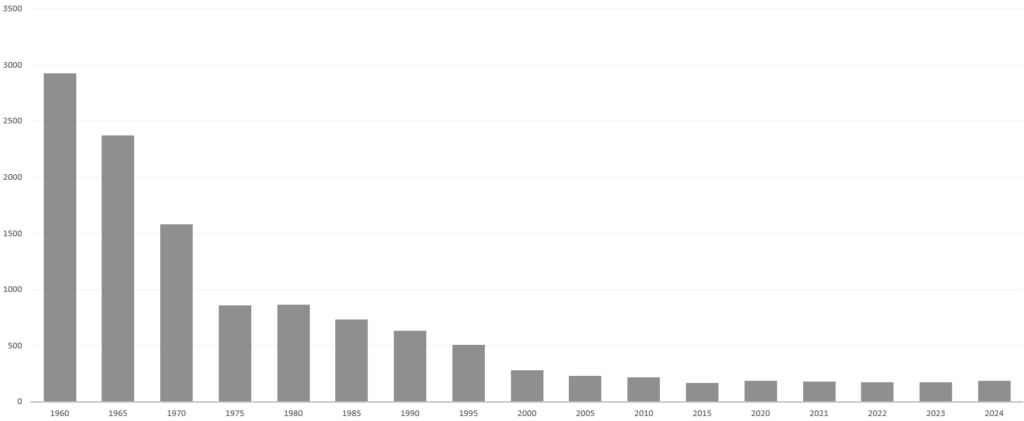

The closest program America has to China’s MCF is the Merchant Marine, a little-known department of the military comprising civilian and federally owned merchant vessels. Under the MARAD’s Maritime Security Program (MSP), these ships can be obtained for the logistical support of a war effort. Their most significant use was during World War II, in which 733 U.S. merchant vessels were sunk by U-boat attacks. Thankfully, these ships were able to be replenished by the United States’ then-functional shipbuilding industry. It is doubtful, however, that the capacity to accomplish a similar rebuilding effort—much less to solicit it—is even possible today. One report published by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics traced the historical quantity of oceangoing U.S. merchant vessels over 1,000 gross tons. In 1960, there were 2,926 of these ships. Now the fleet stands at merely 185 (see Table 1-A).18 Of those 185, just 82 are actively participating in commerce.19 By constraints the MARAD has itself imposed, only 61 of those 82 vessels currently participate in the MSP. And of those 61, just 39 were operationally ready under the criteria the United States Transportation Command set for its “Turbo Activation” sealift readiness test conducted in 2019, less than a tenth of the number of merchant ships lost during World War II.20

Suffice it to say that the United States is comparatively lacking in its sealift capabilities and, given the limited number of shipyards it has to solicit from, is certainly not able to replenish itself in a tonnage war over a practical time frame.

Abuse in the Shipbuilding Industry

So what—or who—is to blame? Some portion of it can certainly be attributed to malice and negligent practice. Austal USA, one of the aforementioned foreign contractors the United States employs to construct its ships, pleaded guilty to charges of fraudulent practice last year. The malpractice it conducted included falsely reporting finances and the obstruction of audits that would have otherwise revealed growing shipbuilding costs. The outsourcing of shipbuilding to foreign entities has no doubt contributed to the depreciation of the United States’ naval fleet, which has nearly halved since the Cold War—decrease from 592 ships in 1989 to 275 ships by 2016.21 Some downsizing after the collapse of America’s largest naval competitor is to be expected, but a decline almost comparable to the one Russia endured after the collapse of the Soviet Union is difficult to comprehend.22

In December 2020, the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations prepared a report to Congress on its long-range plan for shipbuilding. It spans thirty years, starting in 2022 and ending in 2052. The plan’s objectives are to fund the modernization of the fleet and its recapitalization to 356 ships by 2031.23 Despite this objective and the $135 billion that has since been dedicated to accomplishing it, the Navy’s inventory still stands at a mere 296 ships—thirteen ships below the benchmark for 202424 and the exact same number as in 2020 at the start of the Biden administration.25 In 2023, the Navy sent a revised force-level plan to Congress detailing a confident projection of 381 ships by 2045.26 This confidence is misplaced and has not been reinforced by any congressional law to maintain accountability. Without such legislation, the Navy has used these inflated claims to acquire its vast budgetary sums. A 355-ship objective had previously been made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY 2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115-91 of December 12, 2017), but the provision, shown as a note to 10 U.S.C. 8661, includes no enforcement mechanism. As a result, the Navy has been able to make considerable changes to previous projections with impunity, including the net detraction of seven unmanned vessels, seventeen destroyers, five attack submarines, and ten support vessels from its 2025 goal.27 The only projected increase is the addition of four troop transport ships.

Another contributing factor to these adjustments is the unanticipated number of aging and undermanned vessels needing to be decommissioned. The Navy’s projection of vessels to be retired in 2025 went from five in its previous plan to nineteen in its current one. Delays are also rampant. Virginia-class submarines are experiencing contract delivery delays of up to thirty-six months.28 The SSBN Columbia’s delivery has been delayed by more than a year.29 The new Constellation-class frigate’s lead ship is expected to be delayed by three years.30 The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise has been delayed by eighteen to twenty-six months.31 The USS Nimitz, also an aircraft carrier, had been due for decommissioning by 2025 but was delayed by a year.32 Despite improvements in the fleet’s per capita lethality, the Department of Defense’s production line is currently unable to meet its quantitative goals. The previous administration’s Naval Secretary blamed deficiencies on America’s industrial base, leaving out any mention of the gross mismanagement of the Pentagon.

It may not be mere incompetence, though. When the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program was found to be rife with delays, senators began to question its merits. Supporters of the program responded with a lobbying campaign. One prominent voice upholding the reputation of the LCS program is Timothy Spratto, a retired U.S. Navy officer once in charge of material acquisition who now works for BAE Systems, a foreign contractor that runs repair shipyards for Littoral Combat Ships.33 Retired Rear Admiral and Executive Officer of the LCS program James A. Murdoch is another supporter. He leads one of General Dynamics’ programs responsible for the maintenance of those same ships. There is no question, then, as to why many of these failing projects remain with the same contractors committing repeated infractions and delays. Acquisition officers enter an environment where a cushy private-sector job is expected after their time in service is complete. Not wanting to step on the feet of any prospective employers, these officers practice willful negligence against ineffective policies and programs.

Waste in the Shipbuilding Industry

The Biden administration’s attempts to bridge the procurement gap were lackluster at best and destructively counterproductive at worst. Twice in 2024, then–Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro suggested that changes be made in immigration and visa law to allow more foreign workers to replace American shipbuilders.34 MARAD, in its FY 2025 budget request, allotted $262 million to equity and climate change programs—roughly 20 percent of its entire budget—in alignment with the Biden administration’s Justice40 initiative.35 In that 168-page report, “shipbuilding” was mentioned only fifteen times. Meanwhile, there were thirty-one instances of “equity,” fourteen of “diversity,” and twenty-one of “climate change” and “environmental justice” total. Working closely with the United States Merchant Marine Academy (USMMA), which is responsible for the education and training of maritime officers, it dedicated multiple pages to the accomplishments made in “diversifying” the institution. This included the creation of a Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging (DEIB) Office and chief diversity officer position in USMMA’s senior leadership. In stark contrast to the hundreds of millions of dollars given to these woke programs, only $20 million was allocated for the Assistance for Small Shipyards program,36 which is the only program MARAD runs to stimulate the shipbuilding industry.37 No funding was allocated for large ship manufacturing. In a nearly billion-dollar budget, not a single function of MARAD has served to offset the depreciating relevance of America’s shipbuilding industry.

Proposal No. 1: Determine Funding Priorities and Drive Back Shortfalls

Massive deficiencies in the industrial base require a massive overhaul in how funds are allocated. In the past, the Department of Defense ran a buyer’s monopoly on naval shipbuilding and thus the demand for its ships. Its strategy of consolidating contractors to merely two U.S.-based yards offered no opportunity for startup shipyards to form. In theory, this policy was meant to provide more oversight, ensuring maintenance of technological standards. In practice, it has stifled productivity almost completely. The Center for Renewing America, in its FY 2023 budget proposal,38 suggested the allocation of $31.3 billion for fifteen battle force ships to help in reaching a realistic goal of 355 ships by 2031. To resolve the issue of insufficient acquisition, the Pentagon could consider the following stipulations for the allocation of those funds:

- Abolish the Department of Defense’s policy of consolidation.

- Considerably loosen regulations for newer shipyard projects.

- Provide financial incentives for the refurbishment of decommissioned shipyards.

- Restrict retired officers from entering roles where they would have had a conflict of interest in their military service.

Proposal No. 2: Eliminate DEI Programs and Other Woke Initiatives

The Maritime Administration’s previous budget requests demonstrated that its spending priorities were less about sustaining the American shipbuilding industry than they were about enforcing woke regulation and indoctrination. Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy and the next director of the MARAD have the opportunity and authority to eliminate these wasteful policies. Any program that conforms to the Biden administration’s disastrous Justice40 initiative could be submitted for review to ensure compliance with Executive Order 14151 (“Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing”) and Executive Order 14148 (“Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions”). Removing DEI initiatives would not only help USMMA recruit the best and brightest American mariners but could potentially release hundreds of millions of dollars in funding to be redirected towards projects pertinent to the maritime industry and shipbuilding.

Conclusion

There are a total of sixty inactive large-vessel shipyards across the United States. There are also millions of hard-working citizens laboring in low-skill and low-wage occupations. The capacity to rebuild the fleet is still available, albeit dormant and slowly decaying. Revitalizing the fleet calls for simultaneous economic and workforce revitalization. A great deal is being lost to bureaucratic waste, unaccountable expenditures, and detrimentally woke programs. The Department of Defense’s goals and promises are often not upheld and/or are deceitfully constructed to obtain outlandish budgets. America’s shipbuilding industry has been treated as if it is in hospice rather than infirmary care, receiving only the bare minimum to sustain operations while its workers and equipment age into dysfunction. Adversarial nations such as China and Russia are outpacing the United States in assembling strategic industrial bases for their fleets. The Executive Office, in charge of the nation’s defense, has the opportunity to produce a policy and strategy that prioritizes the fleet’s recuperation, and it will be incumbent upon Congress to enforce that recuperation through mandates on spending.

Endnotes

1. Gross tonnage exceeding 1,000 tons.

2. Tim Colton, LaVar Huntzinger, “A Brief History of Shipbuilding in Recent Times,” Center for Naval Analyses, September 2002, p. 5.

3. Tim Colton, “U.S. Builders of Large Ships,” shipbuildinghistory.com.

4. Office of the Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, “State of Competition Within the Defense Industrial Base,” Department of Defense, February 2022, pp. 4-5.

5. Id.

6. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, August 6, 2024, p. 15.

7. Id., at 15-16.

8. Mallory Shelbourne, “CNO Gilday: Industrial Capacity Largest Barrier to Growing the Fleet,” USNI News, August 25, 2022.

9. Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, August 16, 2024.

10. Kwan Wei Kevin Tan, “China Has the Capacity to Build PLA Combat Ships at 200 Times the Rate That the US Can, Per Leaked US Navy Intelligence,” Business Insider, September 15, 2023.

11. Id.

12. Cathalijne Adams, “China’s Shipbuilding Capacity Is 232 Times Greater Than That of the United States,” Alliance for American Manufacturing, September 18, 2023.

13. Tim Colton, LaVar Huntzinger, “A Brief History of Shipbuilding in Recent Times,” Center for Naval Analyses, September 2002, p. 2.

14. J. Blanchette et. al, “Hidden Harbors: China’s State-Back Shipping Industry,” CSIS Briefs, Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 8, 2020.

15. U.S. Department of State, “Military-Civil Fusion and the People’s Republic of China,” April 2020.

16. Conor Kennedy, “RO-RO Ferries and the Expansion of the PLA’s Landing Ship Fleet,” Center for International Maritime Security, March 27, 2023.

17. U.S. Navy, “Large, Medium-Speed, Roll-On/Roll-Off Ships T-AKR,” October 13, 2021.

18. “Number and Size of the U.S. Flag Merchant Fleet and Its Share of the World Fleet,” Bureau of Transportation Statistics, updated May 2024.

19. Duncan Hunter, “The State of the U.S. Flag Maritime Industry,” Opening Statement in Congressional Hearing, January 17, 2018.

20. “Comprehensive Report for Turbo Activation 19-Plus,” United States Transportation Command, December 16, 2019, p. 14.

21. U.S. Navy, “US Ship Force Levels,” Naval History and Heritage Command, 2016.

22. It’s estimated that Russia’s Navy depreciated around 70–80 percent after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

23. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, “Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2020,” Department of Defense, December 9, 2020, p. 7.

24. Id.

25. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, July 25, 2024, p. 57.

26. Sam LaGrone, “Navy Raises Battle Force Goal to 381 Ships in Classified Report to Congress,” USNI News, July 18, 2023.

27. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, “Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025,” Department of Defense, March 2024, p. 20.

28. supra note 25, at 11.

29. Id.

30. Mallory Shelbourne and Sam LaGrone, “Constellation Frigate Delivery Delayed 3 Years, Says Navy,” USNI News, April 2, 2024.

31. supra note 25, at 11.

32. Sam LaGrone, “Navy to Decommission 2 Carriers in a Row, 2 LCS Set for Foreign Sales, Says Long Range Shipbuilding Plan,” USNI News, April 18, 2023.

33. “Timothy Spratto,” LinkedIn profile, accessed March 11, 2025, https://www.linkedin.com/in/tbspratto.

34. supra note 6, at 19.

35. “Budget Estimates, Fiscal Year 2025,” Maritime Administration, U.S. Department of Administration, March 11, 2024, p. 11.

36. Id., at 5.

37. Id., at 4.

38. “A Commitment to End Woke and Weaponized Government – 2023 Budget Proposal,” Center For Renewing America, August 1, 2023, p. 37.